On September 21, 2024, I eagerly woke up for the first Shabbat of the academic year, excited to attend Hillel’s Shabbat services organized by the OU-JLIC branch. After the morning prayers, I headed to the OKT lunch room for the communal meal. As I entered, a new art installation in the space immediately caught my eye—Hillel had introduced an exhibit over the summer, centered on the theme of female rabbis. I found this theme intriguing, but one piece in particular struck a dissonant chord with me.

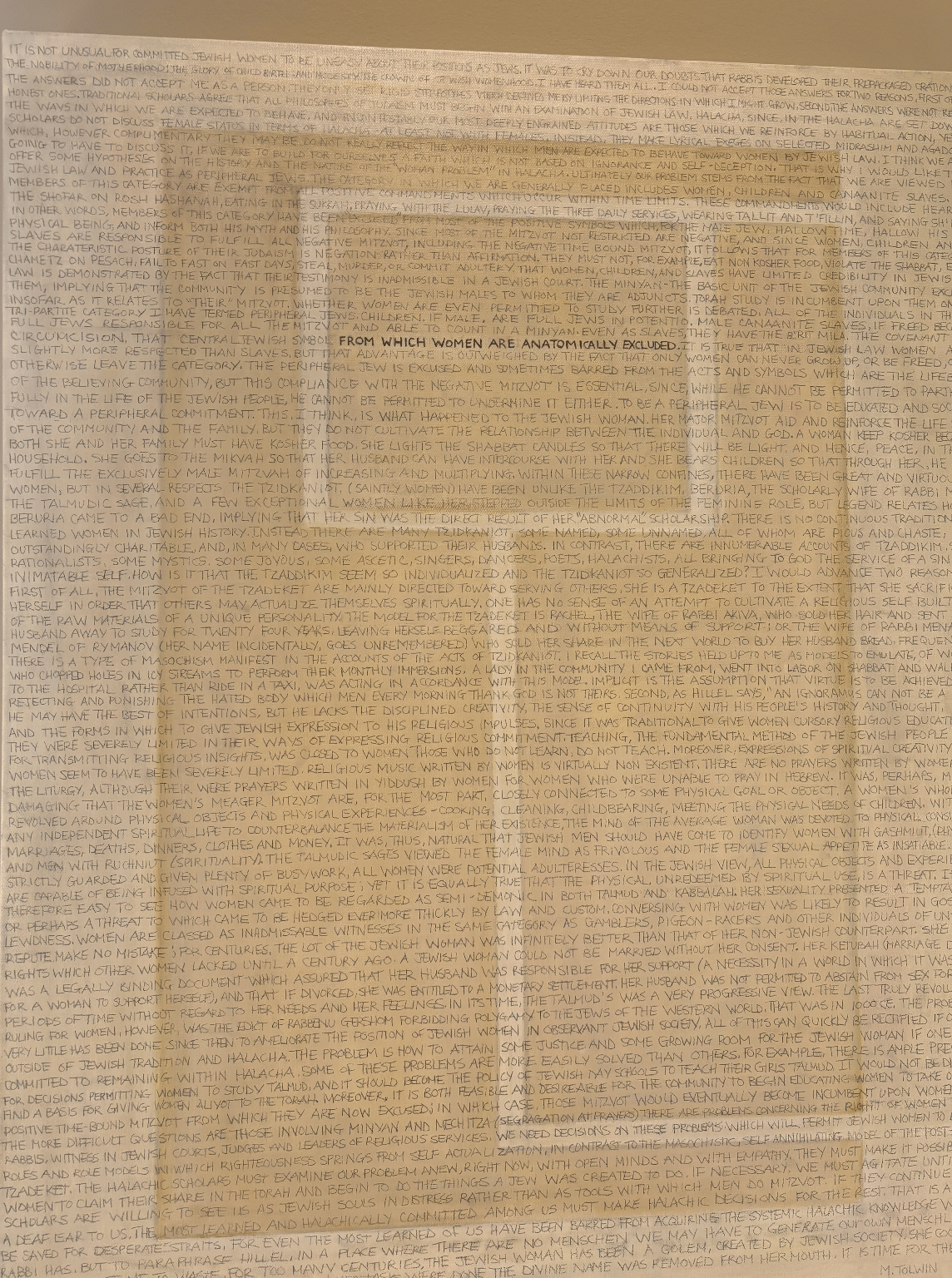

Painting: The Jew Who Was There (2021), oil and pencil on canvas, by Marilee Tolwin

The artwork made several provocative claims, the most jarring being that Orthodox women are “anatomically excluded” from certain roles in Judaism. Upon closer inspection, phrases like “How women came to be referred to as semi-demonic in both the Talmud and Kabbalah” and “Women seem to have been severely limited” stood out. To me, this was not only offensive but contradictory to the pluralistic environment Hillel aims to foster for Jewish students on campus. One Jewish student expressed the sentiment perfectly: “Not only is this particular piece wildly offensive… it is patently false. Designed to resemble a tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, the piece reads more like a rant than a sacred text.”

When I first arrived at UCLA as a freshman, I wasn’t particularly observant in my Judaism, but I longed for a Jewish community. During my second week, I was invited to an Olami Shabbat hosted by the Siskin family. There, I met Melissa Siskin, the rebbetzin, with whom I immediately connected. She became a mentor and a source of inspiration, offering me a traditional and spiritual perspective on Judaism, especially on women’s connection to faith. Together, we created a women’s class that attracted 12 girls, helping us all explore our roles and spiritual identities as Jewish women.

Through this journey, I learned about the remarkable women in Jewish history who served as powerful leaders: Deborah, the first prophetess; Chana, a model of deep prayer and connection to G-d; and Queen Esther, who courageously saved the Jewish people in the story of Purim. I also came to understand that women have a direct and unique link to Hashem. In Halacha, unlike men, we can pray to Him without the need for a minyan, and we have special mitzvot, like lighting Shabbat candles and the rituals of the mikvah. One of my favorite parts of Shabbat is when “Eishet Chayil” is sung, honoring the women of the household.

As a friend of mine pointed out, “In Kabbalah, women are elevated to such a high spiritual level that they are credited with bringing the eventual coming of the Moshiach. The Zohar likens the revelation and glory of G-d to a princess, and each of the ten sefirot, the elements of divinity, have both feminine and masculine aspects. Such a position is far from likening women to the demonic and instead elevates them in a deliberate and meaningful way. Even feminist theologians, like Judith Plaskow, have regarded Judaism as one of the first faiths to radically center women.”

It’s easy to judge what we don’t fully understand. It’s easy to see Orthodox women who cover their hair after marriage or dress modestly and assume they are oppressed. However, learning about the depth and purpose behind these practices is incredibly empowering. It’s also important to recognize that family dynamics play a significant role in how women are treated, and making sweeping generalizations about Orthodox Judaism being universally oppressive is not only unfair but inaccurate.

This raises a broader, modern question: does fulfilling traditionally male religious roles truly define female empowerment? Or can women and men in Judaism, each with their distinct roles, stand as equals in power and spiritual significance?

The views expressed in this post reflect the views of the author(s) and not UCLA or ASUCLA Communications Board.

Cover Image via Canva

Painting by Marilee Tolwin