When the news broke that kidnapped Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit had been released, we celebrated, all of us. My friends and I called and e-mailed home, exclaiming at the news, and joined in the bittersweet jubilation from our Jerusalem apartments, knowing that over a thousand prisoners, among them convicted murderers, would go free — the price paid for a Jew’s life. Israel did not seem to know whether to laugh or cry, and so did both.

When the news broke that kidnapped Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit had been released, we celebrated, all of us. My friends and I called and e-mailed home, exclaiming at the news, and joined in the bittersweet jubilation from our Jerusalem apartments, knowing that over a thousand prisoners, among them convicted murderers, would go free — the price paid for a Jew’s life. Israel did not seem to know whether to laugh or cry, and so did both.

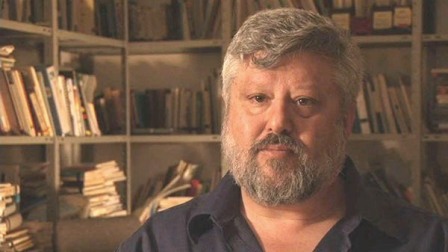

On the evening of Tuesday, February 5th, the UCLA chapter of the Olive Tree Initiative and guests heard from the man who had worked significantly behind the scenes to bring Shalit home. Hosted by OTI, Dr. Gershon Baskin of the Israel-Palestine Center for Research and Information spoke about the lengthy negotiations with Ḥamas that stretched from early July 2006 (six days after the kidnapping) to Oct. 2011. Baskin began with the highly emotional story of the kidnapping and murder of Sasson Nuriel, one of his wife’s first cousins, and his decision to do “everything humanly possible” to save the lives of other kidnapped people, should the occasions arise.

Fast forward nine months to the killings of two Israeli soldiers and the kidnapping of the third soldier in the tank, Sergeant Major Shalit. Baskin received a phone call from a colleague — and Ḥamas member — Muḥammad Migdad, asking him to help open a channel of communication between Israel and Ḥamas. Along with Ḥamas spokesman Ghazi Hamad and the support of Shalit’s parents, they attempted to begin negotiations for a videotape that would demonstrate a “sign of life,” but then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert would not hear of negotiating with a terrorist organization. During the next month and half, Baskin tried further to begin communications, but, “like a manifesto, Olmert refused,” (to put it in Baskin’s words). They changed the agreed-upon “sign of life” from a video to a handwritten letter, which was then blocked by Ḥamas in Damascus. After further pressure, it was delivered on September 9, 2006. After the appointment of Ofer Dekel as head of the Shalit rescue sub-department and the intermediary efforts of Egypt, a tentative deal was reached, but then fell through because of the civil war between Ḥamas and Fataḥ.

In July 2008, a different prisoner exchange was made with the Lebanese terrorist organization Hezbollah: the bodies of two captured Israeli soldiers for five Lebanese militants and the bodies of nearly two hundred Lebanese and Palestinian militants. Among the released was Samir Kuntar, a terrorist convicted of killing five people, including the brutal murders of a four-year-old girl and her father. Kuntar’s return was highly celebrated, and he was later honored by Bashar al-Assad and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, inciting much anger and bitterness in Israel.

After the Arab Spring began in 2010, Ḥamas’ Damascus headquarters were thrown into turmoil. Ofer Dekel had been replaced by Chagai Hadas, who resigned in April of 2011. David Meidan, appointed in his place, was determined to clear up the Shalit kidnapping. As Baskin put it, they had numerous offers of help from various quasi-helpful parties, and “when they cleared the noise from the room, they were left with me.” Ongoing communication with Ḥamas boosted Baskin’s legitimacy, and in July of 2011, they agreed on a prisoner exchange.

People cheered, wept, and tacked up blue-and-white banners with Shalit’s photo that proclaimed in Hebrew, “It is so good that you’ve come home!” They clucked over his pale, weak countenance — Baskin said that he was healthy, but depressed and severely deprived of Vitamin D, having seen the sun once in five years. The public also playfully mocked Prime Minister Netanyahu for his strategic placement in the photos of Shalit’s emotional reunion with his father.

Baskin himself had less-than-friendly jibes toward the prime minister and Olmert. They should have opened communication much earlier, he claims, and should have invested more effort into returning Shalit. He has “no idea what they [the officials on the case] did every day,” and believes that they could have mounted an “Entebbe-style” rescue sweep (like the dramatic liberation of the hijacked French plane en route to Israel that was taken to Entebbe, Uganda) had they acted sooner.

He does not think that Ḥamas’ success with Gilad Shalit will inspire further kidnappings: the cost was simply too high for Hamas. Since the kidnapping, Gaza has been invaded several times and its economy was ruined in the process. It is now an impoverished, cinderblock shell, and its victory was too Pyrrhic to be sweet, he says.

Baskin strongly believes in the possibility of peace in the Middle East. Perhaps, as Gilad Shalit recuperates, his region will as well.