Of all the terms readily associated with the Middle East, “resilient” and “stable” are refrains mostly designated for other regions. However, largely to the credit of the governor of the Bank of Israel, Stanley Fischer, the Israeli economy has managed to navigate times of global economic hardship and regional turmoil and unrest. Naturally, the news of Stanley Fischer’s intent to retire from his post with the Bank of Israel on June 30 marks a watershed moment for one of the few sources of stability in the Middle East.

Of all the terms readily associated with the Middle East, “resilient” and “stable” are refrains mostly designated for other regions. However, largely to the credit of the governor of the Bank of Israel, Stanley Fischer, the Israeli economy has managed to navigate times of global economic hardship and regional turmoil and unrest. Naturally, the news of Stanley Fischer’s intent to retire from his post with the Bank of Israel on June 30 marks a watershed moment for one of the few sources of stability in the Middle East.

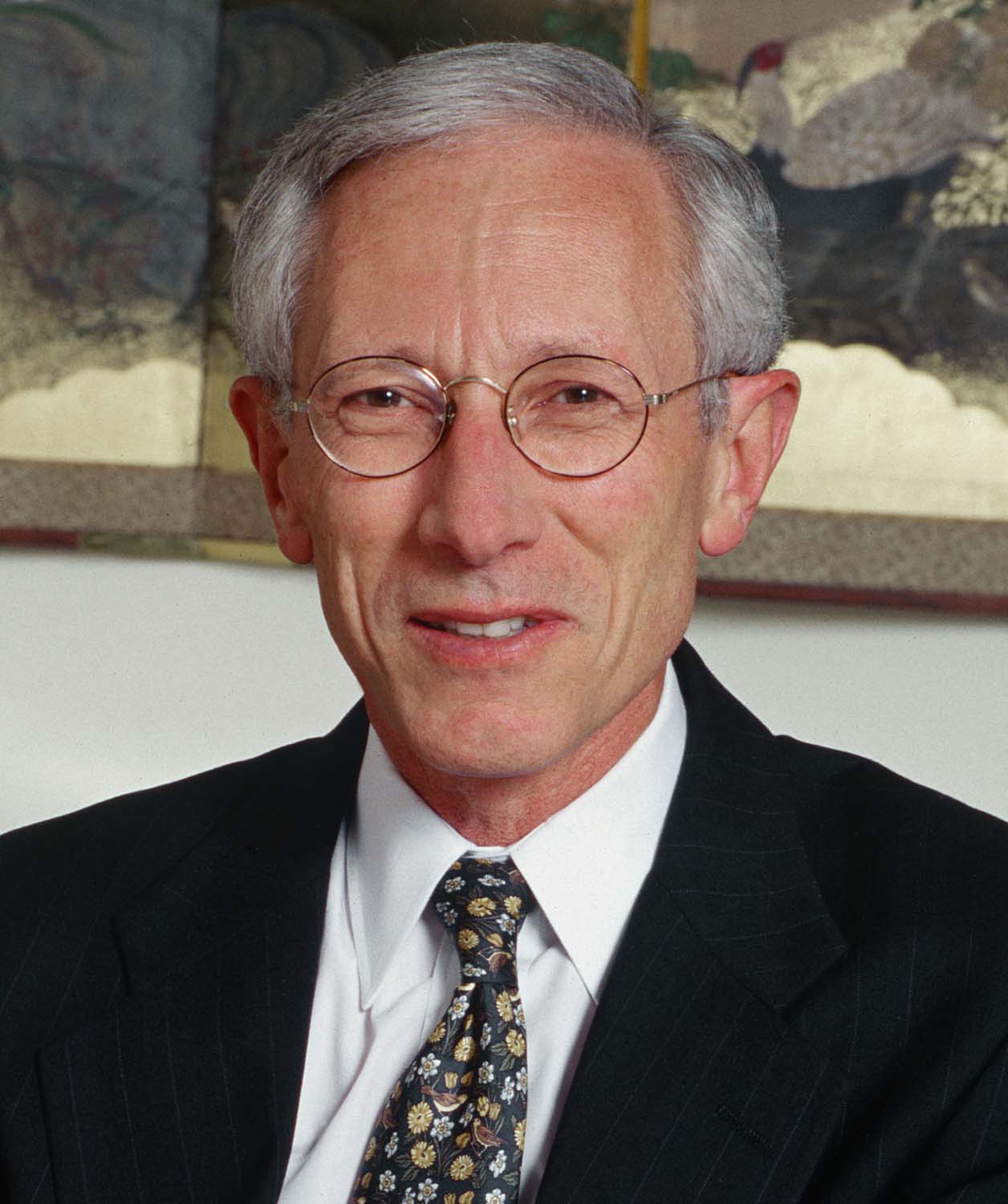

The Zimbabwean native and former First Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund joined the Bank of Israel in 2005 after a lengthy career as a professor of economics at MIT and a leading economist at several international financial institutions, including the World Bank. The financial markets in Israel did not take positively to the news of Fischer’s impending retirement, with 10-year Israeli-issued maturities rising to a two month high of 4.14 percent. Fischer’s policies at the Bank of Israel proved instrumental in aiding the Israeli economy, which recovered at a faster rate than the United States and the European Union.

Fischer can point to an impressive tenure with the Bank of Israel. According to the Bloomberg Riskless Return Ranking, over the past ten years, the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange has returned 13.4%, the greatest rate of return among developed nations. The newly elected government, which in all likelihood will have Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the helm, is now responsible for finding a replacement for Fischer, who was nominated to the post by then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon.

As governor of the Bank of Israel, Fischer’s responsibilities included managing the money supply to promote economic growth, and the supervision of inflation. Under Fischer’s leadership, the Israeli economy was deemed “most durable in the face of crises” and had the “most efficient[ly] functioning” central bank in 2010, according the IMD’s World Competitiveness Yearbook ranking.

However, Fischer’s policies have not come without criticism. The 2011 Israeli social protests voiced concerns over rising costs of housing, cost of living and the increasing gap between Israel’s rich and poor — alleging that monetary policy has allowed the housing industry to overheat. According to the Bank of Israel, housing prices have risen 5.7 percent over the past 12 months, as economic growth has slowed to 3.3 percent; these figures suggest that despite the success of Fischer’s policies, a series of economic obstacles still remain.

With the ongoing civil war in Syria, precarious political posturing in Egypt and tension over Iran’s nuclear program, the growth of the Israeli economy has represented a beacon of stability for the Middle East. Now, with Fischer’s departure from the Bank of Israel, yet another situation of uncertainty looms. Hopefully, the Israeli government will act responsibly in selecting a qualified replacement for Fischer, whose legacy will remain a point of pride for the Israeli economy.