Accusations of “Jew” and “anti-Polish agitator” have not been so openly splashed across Polish newspapers since the heights of National Socialism and communism.

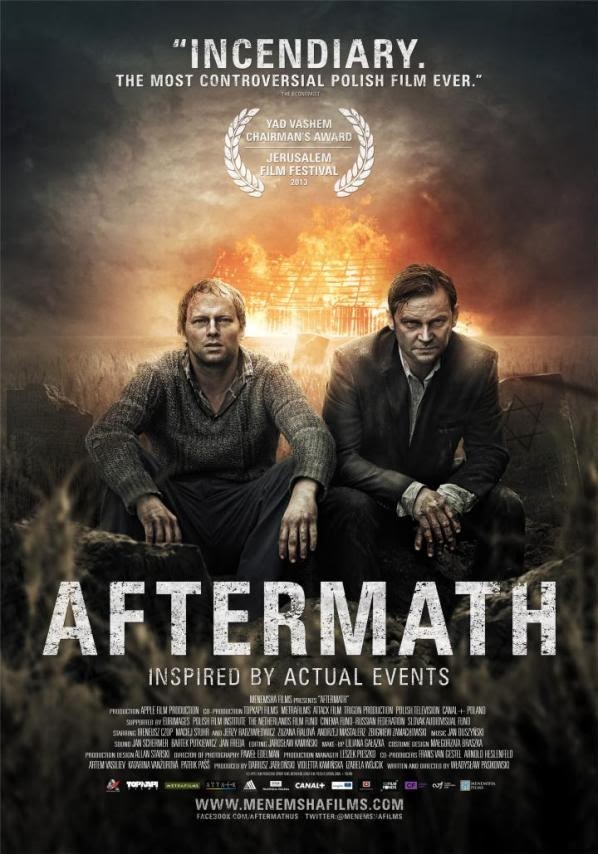

This public outcry has been inspired by Aftermath, a Holocaust-related drama by Władysław Pasikowski, which has been dubbed “the most controversial Polish film ever.” Its actors and director have been accused of Jewishness and of being decriers of the state, “destroying Polish memory,” ruining “Polish-Jewish dialogue” (Polish weekly Uważam Rze), and, most importantly, of “siding with the Jews.”

Unlike a recent Polish film on the same topic — Agnieszka Holland’s Oscar-contender In Darkness — Aftermath does not try to shed light upon acts of goodness by the civilian population, suggesting that although the horror that Jews faced was unfathomable and the crimes against humanity irredeemable, light shines through. There is no hero that combats the forces of Nazi barbarism, no hopeful theme or ending. Instead, Aftermath is the story of two brothers, Franciszek and Jozek Kalina, sons of a poor farmer in a small village in Poland. Franek had immigrated to the United States in the 1980s during the loosening of the communist structure in Eastern Europe, and returns to Poland to discover his brother has been ostracized in the community for attempting, as he eventually does, to understand what had happened to the Jews of their village. The farther the brothers dig into the past, the more aggressive the townspeople become in their efforts against Franek and Jozek.

Although the film was originally advertised as (arguably mistakenly) a “thriller” and naturally pegged as a “Holocaust film” — especially with the brand of the Yad Vashem Chairman’s Award — the Holocaust is never actually represented or even mentioned directly. At the same time, Aftermath manages to rise above even the most powerful titans of the genre: the film seems to the viewer simultaneously more graphic than the blood-soaked Come and See (dir. Elim Klimov, Soviet Union, 1985) and more veiled in its commentary than the unobtrusively poignant films of fellow Polish director Andrzej Wajda. This is because Aftermath is not a Holocaust film. It does not serve as George Santayana’s famous warning; it is a vision of the grim reality that that which was warned about has come to life.

Aftermath cuts to the quick of a matter many films of the genre dare not approach: the present. Most films on the subject of the Holocaust and/or the crimes of the Second World War focus on the past: testifying to it, and, in some cases, revealing it. Aftermath focuses on what happens after that past, after the events and after all of the education. It focuses on the declining — or, more accurately, the unchanging — mores of Eastern European society. What was once called Europe’s refusal to deal with the consequences of the Holocaust and the Second World War is exposed as the willingness to not only forget, but also to return to, the past. The film is a social commentary: the Polish village can be substituted for any in Eastern Europe, the townspeople for anyone, whether in a village or in the capital, whether confronting those who seek the truth in person or through a screen.

Wajda, with whom Powalski collaborated on the 2007 Katyń (another story of war-time massacres in Poland, this time committed by the Soviet government) expressed his pride at such a film coming out from Poland. In contrast, the reaction of Polish nationals — film critics who have panned the movie not for any cinematic flaws but for its inherent message; politicians who refuse to see the movie and want it banned in the country; commentators on internet sites whose remarks bear a sinister resemblance to the policies of the 1940s — only solidifies Aftermath‘s message of secrecy and denial of anti-Semitism and wrongdoing.