Written by Moshe Kahn, Ha’Am staff writer

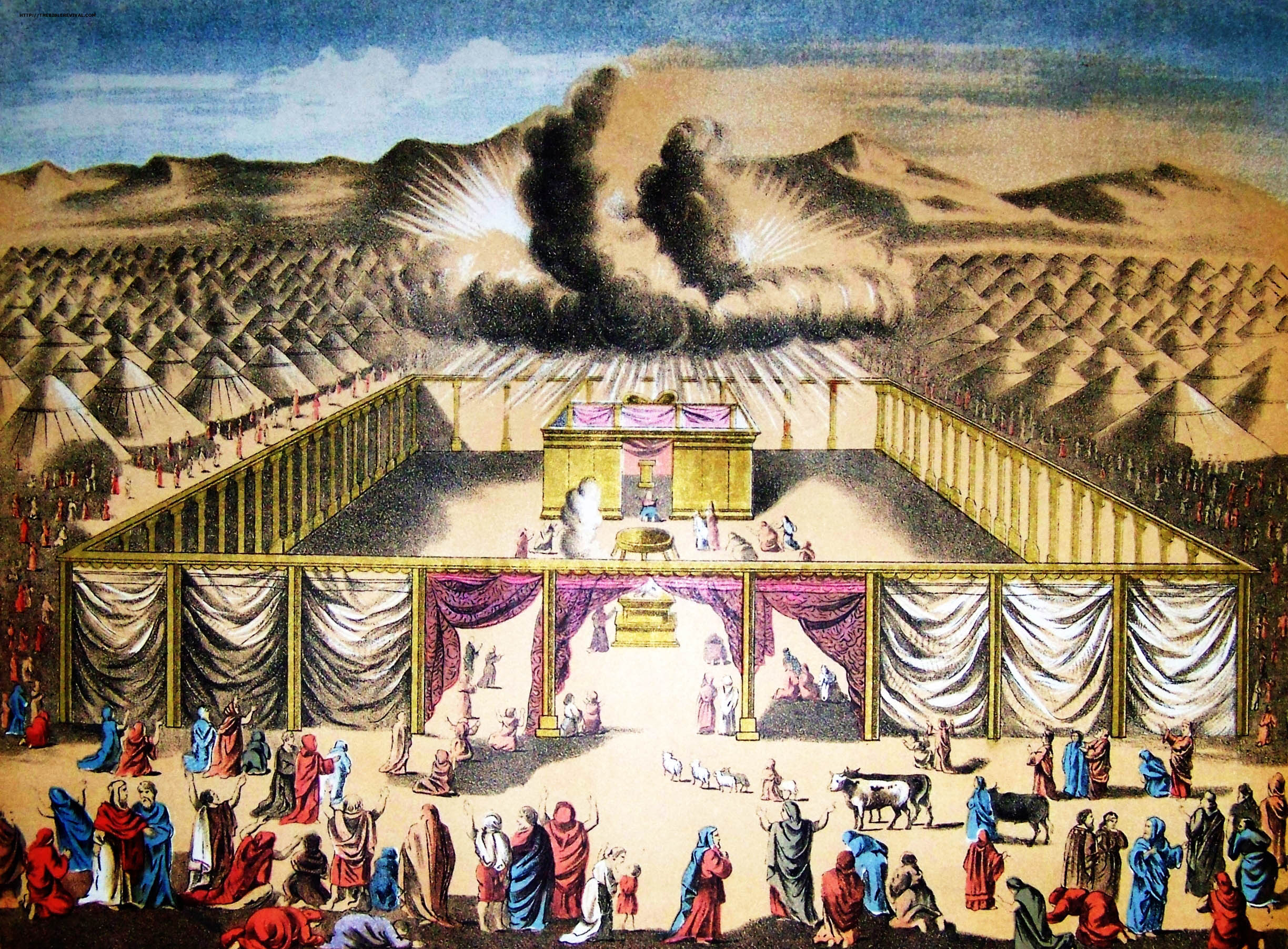

This week’s Torah portion, Terumah (Exodus 25:1 – 27:19), recounts the instructions for the building of the Mishkan (Tabernacle). This portable sanctuary was the focal point of Jewish communal activity until the permanent sanctuary — the Holy Temple (Beit Ha’Mikdash) in Jerusalem — was built. According to our tradition, that which is recorded in the Torah is meaningful for all generations. What then is the meaning of this elaborate instruction manual for the Tabernacle? If it did not already become irrelevant after the Tabernacle was successfully built, it surely became irrelevant after the Tabernacle was replaced by the Temple?

Perhaps the question may be reversed. If the Torah goes to great lengths to tell us the specifications of the Tabernacle, why did we build a permanent structure in its stead? Why did we ever stop using the Tabernacle?

I would like to suggest that we never did stop using the Tabernacle. We have never even stopped constructing the Tabernacle! In order for this to be the case we must recast the Tabernacle as a concept rather than a physical entity.

The parshah (Torah portion) starts with a call for contributions from the Jewish people. Terumah, the title of the parshah, is the term used to refer to these contributions. However, since these contributions are going to be used to construct the Tabernacle, shouldn’t the Tabernacle be mentioned before the contributions? This indicates that the contributions are essential not only for the substantive construction of the Tabernacle, but also for the concept of the Tabernacle. There can be no physical Tabernacle before the physical contributions of the Jews; so too can there be no conceptual Tabernacle before the concept of Jewish contributions.

One of the most essential contributions listed is acacia wood. Unlike many other items which are ornamental, this item is used for the wall beams and so is strictly functional. Since the Jews were commanded to build the Tabernacle in the desert, the question arises: where were they to get this acacia wood? Two answers are given by the commentators; one is principled and the other pragmatic. According to the principled tradition, our forefather Jacob prophetically foresaw this need, so he brought acacia saplings to Egypt, planted them there, and the Jews carried this acacia out with them. According to the pragmatic tradition, the Jews bought the wood from local natives.

These two approaches are reflected in the two following verses: “They should make a sanctuary to Me and I will dwell among them. You should make the Tabernacle and the design of all its vessels according to all that I show you” (25:8-9). The first verse refers to an abstract sanctuary created by the people for a pragmatic use. The second verse refers to the Tabernacle created by Moses based on the principles dictated to him, without an explicit use. The sanctuary which the people create is an abstract entity which is the result of many people contributing various ideas. The Tabernacle which is built in this world is the physical manifestation of this sanctuary filtered through the traditions passed down by our ancestors.

We currently do not have a central sanctuary in which to congregate, but rather small sanctuaries spread across the world. Each of these sanctuaries is the contribution of a particular community. Each varies according to the architectural style and climate of its region, and yet there are essential traditional features which are common. We yearn for a day when we can once again congregate around a single Temple which would act as a grounding for our tradition. Perhaps we must also come to recognize that the Tabernacle is already in existence, each sanctuary representing a different beam which has either been passed down from our ancestors or borrowed from our neighbors. Only once these beams are united may we drape the ornamental tapestries over them and complete the construction of our permanently portable sanctuary.

___________

This article is part of Ha’Am’s Friday Taste of Torah column. Each week, a different UCLA community member will contribute some words of Jewish wisdom in preparation for Shabbat.