Written by Akiva Nemetsky

In the second of this week’s two Torah portions, Parashat Metzorah, we begin by reading about the purification process a metzorah (someone who is punished for speaking lashon ha’ra, denigrating speech) must undergo before being allowed to reintegrate with society. (The punishment is a skin affliction called tzaraat and the person is purified following a period of isolation and the disappearance of the tzaraat.) Immediately following this, the parashah, discusses the offering a metzorah brings to the Temple and proceeds to discuss, in detail, the offering brought by a wealthy metzorah and one brought by a poor metzorah. The detailed description of the poor man’s offering, which seemingly digresses from the overview of tzaraat in general, screams out for an explanation.

“…He shall take two unblemished male lambs and one unblemished ewe…[but] if he is poor and his means are not sufficient…” (Leviticus 14:10, 21).

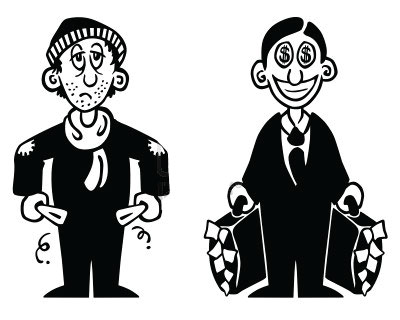

In this verse, the Torah is making a distinction between the offering given by a poor person versus that brought by a wealthy one. The contrast is so stark that if a wealthy individual were to give the offering designed for the destitute, his offering would not be accepted. Clearly, the Torah is setting different standards based on the individual, requiring each person to give only what is within his means.

In the previous chapter, when talking about lashon ha’ra the verse states, “On the day the healthy flesh appears in it [a tzaraat affliction that previously covered the entire body, which was not deemed contaminating], he [the person afflicted] shall be contaminated (Leviticus 13:14).” When scrutinized, this, along with the entire topic of lashon ha’ra, is quite baffling. First, why is it that of all spiritual transgressions God chose lashon ha’ra to be the one to have such profound physical manifestations? Furthermore, why is the process of declaring the afflicted impure carried out so expediently? The Torah uses the extra word ba’yom [“on the day”] to express that the priest must declare the leper impure on the exact day that the irregularity of the skin appeared.

To answer these questions, one must have more than just a superficial understanding of lashon ha’ra. The severity of this transgression lies not just in the fact that an individual spoke negatively about another, but also in that he judged the subject of his words by his own egocentric standards. It is the inability of the perpetrator to see the situation from outside of himself that the real issue lies. Had he exercised at least some degree of empathy and tried to place himself in the shoes of the one he defamed, he would have been significantly less willing to speak ill of his victim.

Herein lies the connection between these two chapters. By establishing different standards of offerings based on wealth, the Torah is effectively conveying this idea, exemplified by the punishment of the metzorah. A person has no right to judge another in the same light that he judges himself because no two people will ever find themselves in identical positions, having faced the same challenges. This was the mistake of the metzorah that led him to denigrate the reputation of his peer. The Torah consciously chose to place these two ideas together because they build on one another; the punishment of the metzorah is meant to serve as an example to the rest of us about judging and speaking negatively about other. Once this idea is internalized, it can be extrapolated to the realm of Temple offerings, leading us to the conclusion that a poor person should not be subject to the same standard of offering as is his wealthy counterpart. Everyone faces different challenges throughout life, and it is up to God, not us, to deliver judgement.

Shabbat Shalom!

____________

This article is part of Ha’Am’s Friday Taste of Torah column. Each week, a different UCLA community member will contribute some words of Jewish wisdom in preparation for Shabbat.