In Hassidic tradition, they tell the story of Rebbe Zusha of Hanipol, a true tzaddik (righteous man), crying on his deathbed. His students and the community surrounded and offered consolation. One student said, “Rebbe Zusha, why do you cry? You have nothing to worry about: you were as wise as Moses and you were as kind as Abraham!” Rebbe Zusha turned to his student and said, “”When I pass from this world and appear before the Heavenly Tribunal, they won’t ask me, ‘Zusha, why weren’t you as wise as Moses or as kind as Abraham?’ Rather, they will ask me, ‘Zusha, why weren’t you Zusha?’ Why didn’t I fulfill my potential; why didn’t I follow the path that could have been mine?”

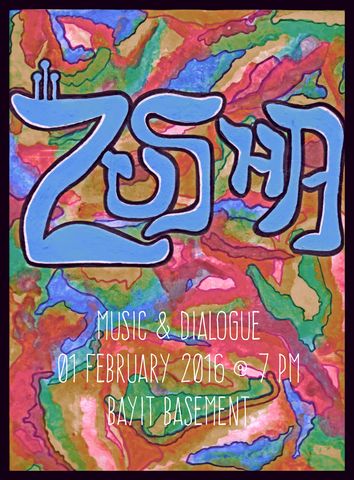

Four musicians sat cramped in the basement of the Bayit on the first night of February. Seated around them were about 40 people from every different walk of life: Jews and non-Jews, religious and secular. All entranced by the niggunim (wordless melodies) of the “neo-hassidic,” “hipster Hassidic,” band Zusha. The band tells the said story of the late Rabbi Zusha as they describe their roots, their background, and what brought them to this moment sitting in the Bayit basement.

Shlomo sat to my left (luckily, he was sitting, since he stands well over six and a half feet tall—dangerously close to the height of the Bayit basement ceiling). He spoke of growing up in a musical family, listening to stories of his parents courting each other through music, and of his eventual love affair with jazz music. On my other side sat Elisha, who spoke of the rich tradition that was Yiddish culture, almost made extinct during the Holocaust but now revived in small pockets of the world like the National Yiddish Theater in New York, where his father Zalmen is the artistic director. Their guitarist Zachariah, or “Juke” as he is known by most, divulged his fascination with reggae music and his past work producing electronic artists. Furthest from me stood Zusha’s newest addition, Max, who spoke of his classical, academic study of bass which he now brings to the very nonacademic approach of Zusha as a whole. Four very different musicians sat playing as one living entity of folksy, intimate music dripping with harmonies that was even more special as it had the excitement and surprise of new, different music yet felt so comfortable, so familiar.

Zusha inspires personal growth and individuality through a communal practice of singing. Each one of them embraces the very essence of the teaching of Rebbe Zusha—to be fiercely individual. Even the videographer who joined them on their world tour, Ora DeKornfeld, is described on her website as “candid, intrepid, and unapologetically herself.” In between songs, Shlomo and Juke described the closeness of the Hebrew words shalom (peace) and shalem (whole) and how peace and wholeness are achieved by recognizing the differences in people, understanding where we are similar, and seeing the world as a larger puzzle with each one of us a unique puzzle piece. The music itself blends choppy reggae-style guitar playing, precise and complex baselines, sung counter melodies made popular in frailich music, and jazz improvisational scat singing in the form of niggunim. Zusha’s members sees their niggunim as prayers, and their wordless nature makes them more approachable and accessible while also allowing for the interpretation of the participant. They bridge the gap between traditional Jewish singing and Hassidic principles of joy and wonder with modern music and personal spirituality.

In the midst of singing and dialogue, Elisha joked with the crowd, “This was not a concert. I am not sure what Jackson told you but this is most definitely not a concert.” Later that night, we stood alongside Ora, reminiscing about the music from an earlier performance. Elisha declared, to the approval of Juke, that “tonight felt different, it felt like we were praying.” He went on to explain that walking into a traditional synagogue, you typically “carpool”: you greet your friends when you enter the synagogue, you walk in with someone talking, then you start to pray and you both fall into your own worlds. However, in the style of singing that happened in the basement of the Bayit, we felt as if we were praying together, maybe with different types of prayers, but through the vessel of the same song.

One of the most important aspects of Zusha is that they are “granters of permission.” By being brutally open about their religious beliefs, their personal perspectives, and the raw emotions they infuse their music with, they grant their audience members permission to do the same. Experiencing Zusha is freeing. As Jessica Jacobs, Hillel’s Engagement Associate described it, “It was liberating to be in a space where I was free to be my true me.” For me, it was liberating to be in a space where it was perfectly okay to be searching for personal identity. The music and the players’ intention filled the tiny Bayit basement and, for a short time, elevated it.

However, the highlight of the night for me was sitting next to two young boys mesmerized with the power of Zusha. In the front row, singing along with every melody, smiling the biggest of smiles, were Nachman Noam and Israel, the sons of the new Jewish Awareness Movement (JAM) couple on UCLA’s campus. They looked on as they sat less than a few feet away from rockstars. But not just any rockstars. These were musical rockstars and spiritual rockstars and righteous rockstars. Earlier in the night when asking Zusha about why they chose Jewish music, they answered, then—almost in unison—turned to me and asked the same question. To a crowd of strangers, I described my own personal “Revelation at Sinai” moment when I first sat looking up at the stained glass ceiling of our shul, singing with Dan Nichols, a Jewish musician. When I saw Nachman Noam and Israel, I recognized the look they gave Zusha. It was the look I had nearly 10 years ago to the date when I first met Dan and he sat with us and sang. He inspired me to wrestle with my Judaism, to love my Judaism, to practice my Judaism, and eventually choose the path of helping others find their own Judaism. While we may not have received the holy word directly that night, I do believe for a few hours in the Bayit basement, the singing was awe-fully beautiful atop the mountain.

Graphic created by Rivka Cohen.