This week’s Historical Ha’Am is another informational one. While we are all familiar with traditional head coverings such as the yarmulke, it is likely that not everyone knows the history behind them (I know I didn’t before reading this article!). So, please allow to Debbie Rothberg’s 1996 article teach you some Jewish history about a long-lasting tradition:

“You may be strolling down the Champs Elysées in Paris or hiking up K2 in Nepal when you suddenly spot a man wearing a skullcap and a woman with a scarf wrapped around her head, and you immediately think to yourself, “They’re Jewish.” Kissui rosh, head coverings for men and married women, are recognized trademarks of the Jewish community. Head coverings for married women can be traced back to a commandment written in the Torah, while men’s head coverings started as customary garb, and over time became an identifying tradition. Even with these distinctions, head coverings for both Jewish men and married Jewish women share a common purpose, reflecting humility before God and the general public.

Jewish men were not always required to cover their heads on a daily basis in order to express their humility before God. Alfred J. Kolatch, author of The Jewish Book of Why, claims that the earliest mention of any head covering in the Torah is in reference to the wardrobe of the kohen gadol, the High Priest, who wore a mitznefet, a cap, on his head when performing special duties in the Beit Hamikdash, the Holy Temple. The Priest only wore this hat while making sacrifices or performing other priestly duties. Some scholars say the reason Jewish priests wore head coverings was to distinguish themselves from non-Jewish priests who also offered sacrifices to their gods at that time.

Although no law existed regarding men’s head coverings in Talmudic times, it was customary for all men to wrap a kerchief around their head upon waking up and reciting the blessing, “Blessed is He who crowns Israel with glory” during the morning service. Scholars wore special kerchiefs in order to distinguish themselves from the general population. Kolatch retells a story concerning Rabbi Chia bar Abba, who reprimanded one of his students for wearing the standard kerchief, rather than a head covering designated for scholars. Since scholars were immersed in spiritual learning throughout the day, they were keenly aware of the existence of God. This awareness led them to have a greater fear of God, and, therefore, a greater sense of humility towards Him. Kolatch states that it made sense that they would eventually take it upon themselves to cover their heads throughout the day.

The Talmud recounts a story of Rav Huna, who would not walk even a few feet without a head covering. His rational(sic) for this practice was that it attested to his belief of God’s omnipresence above his head. An anecdote about the mother of a Babylonian scholar named Nachman ben Yitzchak is told in tractate Shabbat of the Talmud. The Talmud relates that astrologers told the scholar’s mother that he would become a thief. In order to prevent this occurrence, she told Nachman to always keep his head covered so that he would fear God continually and ward off his inclination to steal from others.

Soon, head coverings became daily garb for the male Jewish population who had been exiled to Babylonia after the destruction of the Holy Temple although there was no official law requiring this practice. Kolatch claims that Jews were used to seeing non-Jews with their heads uncovered, adn as a result associated an uncovered head with Christianity. By covering their heads, Jews were able to preserve their cultural identity and distinguish themselves from their Christian neighbors. Soon men who failed to cover their heads were looked upon as being negligent of halacha, the Jewish code of law.

Today women who attempt to follow halacha in its strictest sense cover their hair after marriage. In Biblical times, unmarried women engaged in this practice to promote a certain level of modesty. In Bamidbar (Numbers), Chapter five, the Torah recounts the procedure to deal with a woman suspected of committing adultery. Part of the process of humiliation to induce her to tell the truth about her crime involved the Priest uncovering the woman’s head. This indicates that exposing a woman’s hair was a humiliating experience. In Talmudic times married women began to cover their heads because rabbis claimed hair was “sexually exciting.” Kolatch claims that a man was even allowed to divorce his wife if he found her outside with her hair uncovered.

The Talmud tells a story of a woman who believed that she was blessed with seven sons for having never let the walls of her own house see her hair uncovered. Making oneself less attractive by covering one’s hair is believed to instill a sense of modesty and to distinguish married and single women. Such a distinction lessens the possibility of a man becoming attracted to a married woman, and thereby decreases the chances of extramarital affairs, because by covering her head the woman is constantly aware of her married status, which may deter her from engaging in adultery. On the other hand, for singles of both sexes, this is a signature system to promote relationships between available partners.

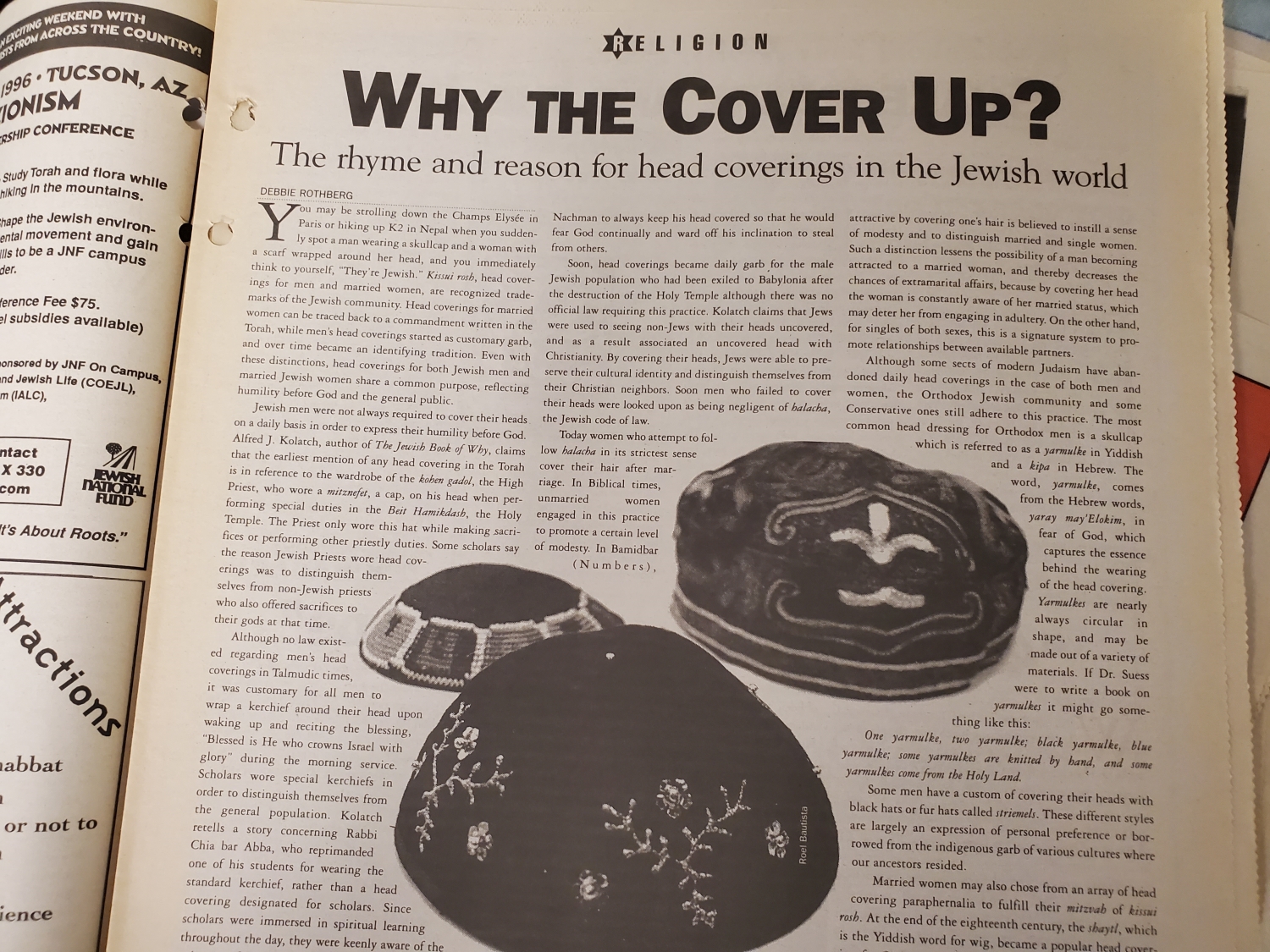

Although some sects of modern Judaism have abandoned daily head coverings in the case of both men and women, the Orthodox Jewish community and some Conservative ones still adhere to this practice. The most common head dressing for Orthodox men is a skullcap which is referred to as a yarmulke in Yiddish and a kipa in Hebrew. The world, yarmulke, comes from the Hebrew words, yaray may’Elokim, in fear of God, which captures the essence behind the wearing of the head covering. Yarmulkes are nearly always circular in shape, and may be made out of a variety of materials. If Dr. Seuss were to write a book on yarmulkes, it might go something like this:

One yarmulke, two yarmulke; black yarmulke, blue yarmulke; some yarmulkes are knitted by hand, and some yarmulkes come from the Holy Land.

Some men have a custom of covering their heads with black hats or fur hats called striemels. These different styles are largely an expression of personal preference or borrowed from the indigenous garb of various cultures where our ancestors settled.

Married women may also chose(sic) from an array of head covering paraphernalia to fulfill their mitzvah of kissui rosh. At the end of the eighteenth century, the shaytl, which is the Yiddish word for wig, became a popular head covering for Orthodox married women. However, not everyone agrees that wearing a shaytl, fulfills the Jewish objective of modesty since a wig may make a woman look more appealing rather than emphasizing her modesty. Some women merely cover their hair with a tichl, a large scarf. Women who want to make sure their hair does not show may choose to shave their heads before donning a tichl. This practice is limited to a very small sect of ultra-Orthodox Jews.

The covering of one’s head began as a sign of humiliation. Today, however, it serves as a distinguishing religious ornament adorning the heads of many Jews. Whether a man chooses to cover his head with a streimel or a Mickey Mouse kipa, or a woman chooses a hat, a wig, or a tichl, kissui rosh is a tradition that many traditional Jews say they would never give up.”

-Debbie Rothberg, February 1996