In high school, I remember my algebra teacher used to tell our class: “to subtract a number, add its opposite.” At the time, I appreciated the advice only for its cliched simplicity.

As I got older, this statement stuck with me. When I began college, I realized the statement could take on an entirely different meaning.

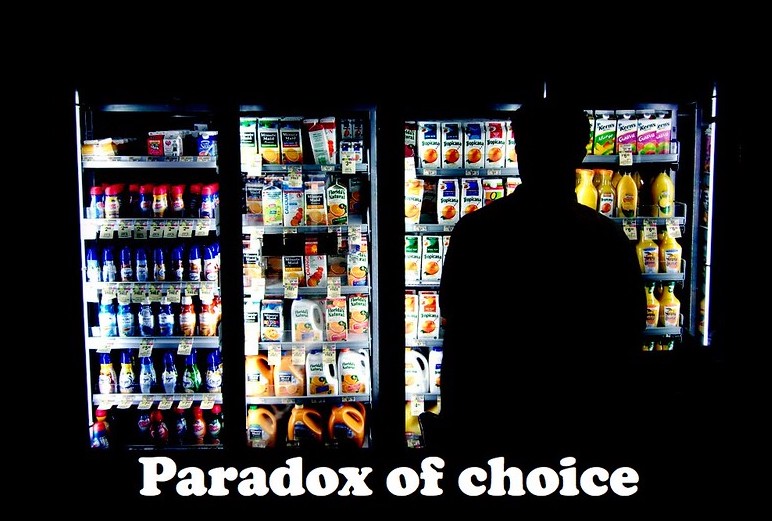

A few years ago, I read a book called “The Paradox of Choice” by Barry Schwartz, which he wrote back in 2004. In it, Schwartz argues that increases in consumer choices, personal freedoms, and the decisions we face may actually have a deleterious impact on our well being.

Schwartz’s ideas strongly resonated with me. Indeed, our society prizes this concept of “more.” Often, and especially in our modern age of instant gratification and consumerism, we are told that the answer to most of our problems is simply “more:” that we need a better job, a better car, more televisions, more academic degrees, or just more stuff in general. Only after acquiring that new, cutting-edge kitchen or trendy cosmetic product are we supposed to become satisfied with what we have.

For example, when the New Year approaches, people make resolutions–adding new commitments to their lives. They might want to learn a new language, go to the gym, start a hobby, or introduce new ideas and habits into their lives.

Of course, this hunger for more is, by definition, quite insatiable. Chasing material, achievements, or accolades only as a means to an end will often leave us feeling unfulfilled.

Ironically, it is actually subtraction–removing tasks, activities, and perceived obligations– that serves to add meaning and value to life. Drawing us closer to what matters most, subtraction enhances our relationships, reinforces our responsibilities, and makes us better versions of ourselves.

In other words, less is more. Schwartz also distinguishes between so-called “maximizers”– those who only accept the very best–and “satisficers”–those who are content with just “good enough.” He cites a myriad of studies that demonstrates that so-called “maximizers” experience less satisfaction, more regret, and overall worse well-being than those who learn to be satisfied.

Judaism teaches that the secret to happiness, elusive as it is, is found when we are able to stop chasing the illusion of more. In the book of Pirkei Avot, Ben Zoma, a rabbinic sage from the first and second century, is famously recorded as saying: “Who is happy – the one who rejoices in his lot.”

The wisdom inherent in this teaching is easy to understand but difficult to internalize. In a society that praises the novel, grand, and frivolous, hardly anyone truly thinks they can enhance their lives through reduction.

Here lies the truth contained in my math teacher’s seemingly unassuming statement. Subtraction, as she taught, is a form of addition itself. When we take away, we are also simplifying. Through this, we can add value to and appreciation for our lives.

In my experience, I have learned to emphasize just how much we can enrich our lives through subtraction. This means that we can make our lives more meaningful through simplification, and learning to rejoice by virtue of that which we do have.

Being content with one’s lot is a major step towards achieving gratitude, what Cicero called the “mother of all virtues.” Gratitude internalizes those blessings that have been bestowed upon us and recognizes how fortunate we are for the people, resources, and experiences that we have in life.

When we express gratitude, we reflect inward instead of gazing outward. We learn to be thankful and appreciative for our portions. We can work toward achieving inner peace, and begin to count our blessings.

I’ll start. I am grateful for my algebra teacher’s maxim, one that has benefited me inside the classroom and out.