Perhaps no Israeli institution has garnered as much criticism lately as the Israeli Rabbinate. In the last several weeks, a series of scandals and controversies have left the Rabbinate reeling under intense public scrutiny. Among several recent controversial decisions is the Israeli Rabbinate’s rejection of letters confirming emigrants’ affiliation with Judaism from a Riverdale-based Modern Orthodox rabbi, Avi Weiss.

This past Thursday, the Nazarian Center for Israel Studies hosted a lecture in Bunche Hall given by Professor Alexander Kaye, of Princeton University, on the historic relationship between the Rabbinate and the Israeli government. As Professor Kaye outlined, longstanding tension has existed in Religious Zionist communities that predates the creation of Israel. Governed by both Jewish religious law, namely Halachah, and governmental law, Religious Zionists have taken several approaches towards reconciling these often-conflicting sources of law.

In fact, according to Professor Kaye, three models for coexistence between these seemingly conflicting sets of laws emerged early-on in Religious Zionism. The first, which Kaye termed the “Holy Rebellion,” places an emphasis on the Jewish nation and seeks to utilize Halachah as a means of promoting the Jewish nation. The second, developed by Religious Zionist Rabbi Shimon Federbush, drew on the American principle of separation of church and state to argue that in Israeli society, a separation should differentiate the Halachic sphere from that occupied by the government. Lastly, the most prominent model, according to Kaye, is that of “a Jewish state which is ruled by religious law.”

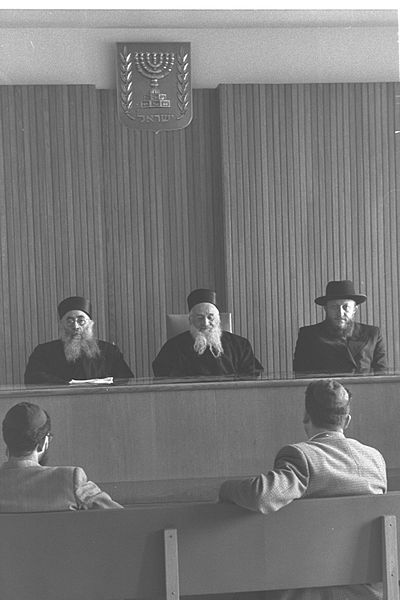

Historically, the third model of emphasizing Jewish law has emerged most prominently in recent years, according to Professor Kaye. In Israeli society today, religious courts largely govern civil matters such as marriage, divorce and other family-related issues. However, the adaptation of Halachah to fit the needs of a modern state has required some creativity. For starters, the precedent in Jewish law for governing a nation state is largely specific to a monarchy. Other changes also occurred in the composition of Jewish religious courts. The position of the Chief Rabbi was introduced by the British during the British Mandate in Palestine and has subsequently remained in place throughout the duration of Israel’s existence. Moreover, previously missing from rabbinic courts was an appellate court, which was also introduced by the British authorities. These changes among others, according to Professor Kaye, reflect an effort to creatively adapt Halachah to meet the needs of the modern state.

While the relationship between religious institutions and the state of Israel has of recent been fraught with tensions, Professor Kaye’s lecture highlighted the historic nature of these strained relations. Nevertheless, as Kaye suggested, there is cause for optimism. Kaye notes a growing trend in religious diversification in Israel and a growth in willingness to explore new alternatives among some of Israel’s Jewish religious leaders. The confluence of these two trends leaves open the possibility that a future agreement might resolve some of the inherent tensions between religious and governmental institutions in Israel.