Are you a world-renowned painter? Perhaps a top-notch doodler? Do you keep a sketchbook? Does your mom keep your drawings on the fridge? Have you ever gotten a gold star for an art project? Did you ever wish you had? If you answered yes, or even maybe, to any of the above questions, you’re in luck! This quarter, Ha’Am is handing out stickers, cookies and even a chance to be showcased in our quarterly print issue!

ARTiculations is Ha’Am’s very first ongoing art exhibit. We will accept submissions from students all quarter long, and each week, one piece of work will be published on our website. One to two pieces that especially resonate with us will even get a chance to be featured in our print issue, coming out November 16th.

You might be asking yourself: who are the masterminds behind this clever idea and what qualifies them to judge what is or is not art? Fear not, for we are mindful and considerate, and will accept and appreciate and submission, regardless of whether you’ve worked on it for years, or just during the last dreadful minutes of class. We would love to share the beautiful river of creativity flowing through your mind with our readers.

The only requirement is for each submission to be an original work of art with a Jewish element. For the “–iculation” component of ARTiculations, we ask for just a short bit about your piece. We would also appreciate a little bio about yourself, but that’s optional, especially if you would like to stay anonymous. All submissions and questions should be sent to [email protected].

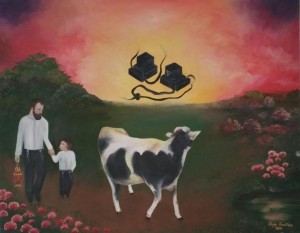

For our very first submission, we are honored to share with you a painting done by an incoming transfer student and our new staff writer, Chaya Leah Esakhan.

The Content Cow. Oil on canvas, 20 X 24, circa 2010

The Content Cow. Oil on canvas, 20 X 24, circa 2010

“You shall put these words of mine on your heart and on your soul; and you shall tie them for a sign upon your arm, and they shall be as totafot between your eyes.” – Deuteronomy 11:18

“My commitment to Judaism is strung by the sacrifices of Jews during the Holocaust and that of my father. Growing up I heard a plethora of stories on resilience and servitude. I recall hearing one story of a Jewish man sacrificing his dear life by bringing a pair of tefillin (phylacteries) and a prayer book inside his boots into the concentration camp from the ghetto. He would, during the Holocaust, provide other inmates the opportunity to fulfill the mitzvah of putting tefillin on the arm and head. I recall another miracle of my father dodging bullets as he escaped Iran through Pakistan in the back of a pickup truck. For what purpose? To come to America and serve G-d freely.

After my brother’s bar mitzvah, I pondered on the significance of tefillin. I imagined a father teaching his son about the commandment from Exodus and Deuteronomy to wear tefillin as a sign and remembrance that G-d brought his children to Israel out of Egypt. I imagined the father and son fearlessly traveling in a forest because their only fear is G-d. He carried a fiery lantern, a symbol of his soul and all the souls before him. I imagined their cow walking ahead of them towards the water, a symbol of Torah, like water, also vital and life-sustaining. I imagined the cow looking out into the horizon knowing his near future. His skin will be used for the tefillin’s housing boxes and straps, his hide for writing parchment, his tail hairs as binding for the four parchments containing biblical verses and even his tendons for sewing thread. The cow is content for he knows that the sacrifice he will make, like many before him, is for the greater and G-dly good.”

Chaya Leah Esakhan is a transfer student at UCLA majoring in Physiological Sciences and minoring in Gender Studies. As a little girl, she had a passion for art, even though her fellow kindergarteners poked fun of her haphazardly-drawn heart. When she was in the first grade, her father heard an advertisement over the Persian Radio 670 AM of an art class in Westwood. He signed her up right away and the rest was history. She took fine art training in drawing, oil painting and watercolor for ten years under Rama, a Muslim-born woman. Their relationship sparked her belief in the power and possibility of religious coexistence. Chaya also taught art for four years, but rather than pursuing a full-time career in the arts, she plans to use her visual capabilities to excel as a future doctor of the human body, the ultimate artist’s canvas.