Over the summer, I had the privilege of reading the biography of former Iranian Jewish leader and businessman Habib Elghanyan, “Titan of Tehran,” written by his granddaughter Shahrzad Elghanyan. In her book, Elghanyan traces her grandfather’s rags to riches backstory, spanning his personal life, success in business, and the events surrounding his brutal execution at the hands of Islamic extremists during the 1979 Islamic Revolution, which led many Iranian Jews to flee their home.

Habib Elghanyan was born in 1912 in Sar-E-Chal or “the edge of the pit,” Tehran’s ghettoized Jewish quarter. While his parents were among the poorest of the thousands of Jews living in Tehran’s Jewish Quarter, they managed to provide their son with access to an education that would improve his life. During his youth, he began trading second-hand clothing and watches, working with his six brothers to scrape anything that would help them escape poverty, sickness, and even violent riots inside Tehran’s Jewish ghetto.

After years of struggle and hard work, Habib became an expert in mining, real estate, construction, and aluminum. However, the thing that made Habib the most accomplished businessman and philanthropist in 20th century Iran was his introduction of the plastic industry to Iran, where he founded Plasco company and constructed the first ever private-sector high rise in Iran. As Habib began to rise in prominence in Iran, he slowly became a leading figure among the 100,000 Iranian Jews. His success brought great pride to the Iranian Jewish community, giving generously to charities in Iran and Israel, setting up schools, and helping many other Iranian Jews become prosperous and at home.

Part of his success, and the success of many Iranian Jews, was the close relations with the ruling Iranian monarch, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, and officials like Iranian Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda. The Shah, like his father, envisioned a Westernized Iran where all ethnic groups flourished and prospered under his rule, making the country powerful economically, socially, and militarily. The Shah’s 1963 “White Revolution” reforms could not have been achieved had it not been for Iranian Jews like Habib, who devoted their time and resources to help with economic modernization, trade, labor, agriculture, and many other advancements.

Habib and other leaders of the Iranian Jewish community also helped the Shah strengthen his relations with the Jewish state of Israel, which generated trade, oil, and military cooperation between Israel and Iran.

While there were many successes in Habib’s life, the author also explores the antisemitism that he and many Iranian Jews faced in a country largely dominated by a Shiite population with a radical clerical establishment. Even though Habib created jobs and opportunities for Muslims in Iran, many still held antisemitic conspiratorial sentiments against him and others like him, accusing the Iranian Jewish community of working against Islam, spying on behalf of Israel, and even controlling the Shah and his government.

In an April 1964 speech to his followers, Ayatollah Khomeini told his followers that Habib and many other Jewish leaders in Iran were “Israeli agents” who controlled the country. In his speech, Khomeini stated that the Elghanyan family, among others, were “among those mediators of world Zionism who resided in Iran.” At the time, Habib, like many other Iranian Jews, thought nothing of the cleric’s comments.

When things in Iran began to take a turn for the worse and disorder began to foment in Iran, Habib and many other Jews reassured friends and family that the Shah’s regime was stable and would not fall. Yet, as things got worse in Iran and some Iranian Jews began to flee the country, Habib decided to stay, even though his closest friends and family members begged him to leave his home.

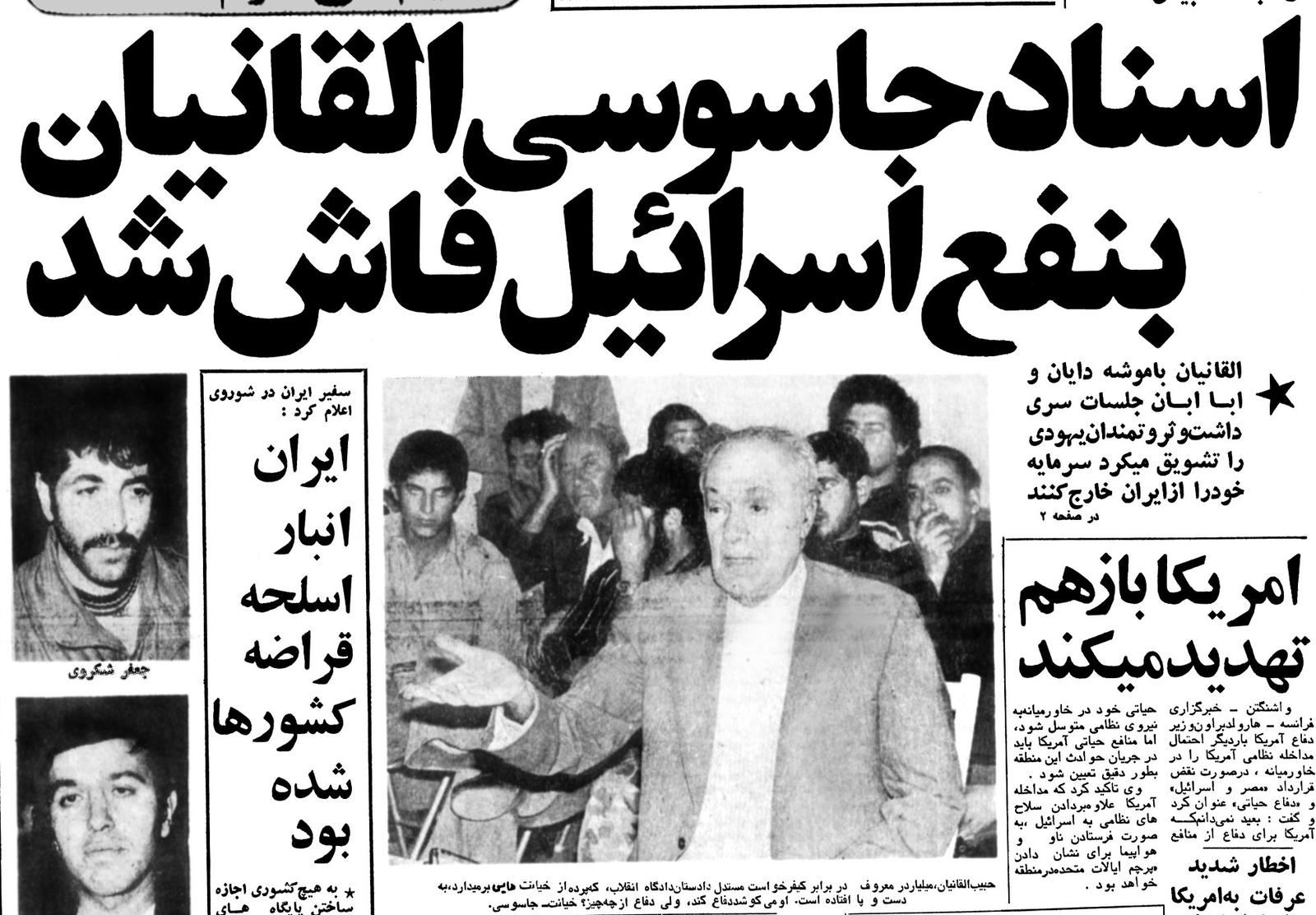

A month after Khomeini’s return from exile to Iran, Habib was arrested and tortured in Qasr prison and eventually put on trial by an Islamic kangaroo court and accused of being a “Zionist spy.” The author leaves no details about her grandfather’s hours in Qasr prison and on trial and describes what it was like for her and her father to reach Habib and get him out of the sham trial. Even though Habib tried to defend himself from the charges lobbied against him, the court found his statements unconvincing and sentenced him to death by firing squad.

As a result of his death, many Iranian Jews fled their homes, taking with them whatever they could and settling in the United States and Israel, where they could escape the newly created Islamic Republic. Readers will be moved by Habib’s life and success, learning what life was like for Jews in Iran before the revolution occurred and why so many have a nostalgia for the Shah’s rule. Readers will understand the perspective of Jews like Habib, who were patriotic and loyal to their country and refused to leave their homes in the face of adversity.

Shahrzad Elghanayan’s “Titan of Tehran” is a must-read book for all younger Iranian American Jews who want a perspective on what life was like for Jews living in Iran and how individuals like Habib managed to help make one of the fewest Middle Eastern countries into a safe haven for Jews before its transformation into one of the most antisemitic regimes today.

“The views expressed in this post reflect the views of the author(s) and not UCLA or ASUCLA Communications Board.”