As much as I hate to admit it, I am an urbanite. I enjoy spending time away from the city, but going on a hike is somewhat of a hassle. So when my friend told me about a nature film she was screening at UCLA with the help of the Campus Events Commission, I jumped at the opportunity. I got to view all of the world’s splendors and remain comfortably cross-legged in a climate-controlled auditorium!

The movie is Disneynature’s Bears, which chronicles the first year in the life of two baby cubs in Alaska. The mother nurtures and guides them, teaching them how to survive in the wild while protecting them from various external threats.

The story is captivating and the shots are breathtaking, so superficially the movie was enjoyable. But there was something gnawing at me while I watched it, and I walked away feeling somewhat robbed. Since then, I have been thinking about my issues with the movie, and how to properly express them.

In the past, Disney has been blamed for reinforcing gender roles and racial homogeneity (among other faults). The new crop of Disney animations seems to be aimed at correcting this. However, these issues really stem from Disney’s tendency to reduce complex issues for the sake of fitting a story into its cheap plastic mold, which has the following characteristics: a clean story arch consisting of a strong dose of goofyness, characters the audience can relate to (the heroes), and other characters (the villains) who attempt to ruin the day of the heroes — all of whom may be easily turned into merchandise.

If you do away with the intricacies of an issue as nuanced as gender, then you are bound to upset people who pay close attention to these issues. It is difficult to imagine Disney solving this except by dissolving itself, and I would surely not advocate doing this. The Disney enterprise is valuable insofar as it is an art form, a commercial hub, and an inspirational attitude that uplifts many people. And besides, Disney is so closely linked to the American ethos from which it emerged that if it would collapse, a different entity would inevitably fill the void.

This is not to say that Disney is off the hook, but rather that Disney is not deserving of wanton criticism. If one wants to truly fix the problem that Disney poses, one would have to change American culture such that Disney would become irrelevant. But that is a difficult undertaking. Instead, I will attempt to point out potential problems that arise when applying the stereotypical Disney formula to Nature documentaries.

There is a certain level of reverence which Nature commands. No matter how self-involved a person is, the sudden embrace of a sweeping landscape is mesmerizing. How long does this feeling last, before it is flittered away by the human symbol system and emerges as the words ‘that’s beautiful?’ After the words are uttered, there is no returning Nature to its former glory, for it has been anthropomorphized. What becomes important about Nature is not Nature in its own right, but Nature as humans perceive it.

Contact with Nature is contact with that which is the same and yet totally different from ourselves. In this respect, Nature simultaneously instills one with a sense of fullness (I am part of something so vast!) as well as humility (I am a tiny entity with enemies enveloping me!). If Nature is reduced to that which humans can relate to, then this balance is offset, resulting in the unimpeded swelling of the ego. The movie Bears does not stop at this reduction, but goes even further in reducing Nature to that which Disney can relate to.

The movie begins with shots of the newly born babies, but just as one begins to wonder at the image with which one is unfamiliar, the narrator’s voice breaks the moment. The narrator, it should be mentioned, is John C. Reilly, a comedian who typically plays ‘stupid’ characters and whose voice is unmistakably silly. The narration constantly projects human thoughts, desires and activities onto the bears, which is the source of a lot of humor. Then the movie ends, and alongside the credits run “behind-the-scenes” clips, in which the filmmakers are revealed.

The bears have become inconsequential. What matters is the spectacle which their growls and chases provide and the laughs evoke at their expense. The story happens to involve bears, but it is only because we humans are able to use our tools to command these animals that anything useful is derived. It is the old story of the might and power of Humanity, of our ability to dominate the world and all its inhabitants. It is the story that Prophets have been arguing against for thousands of years.

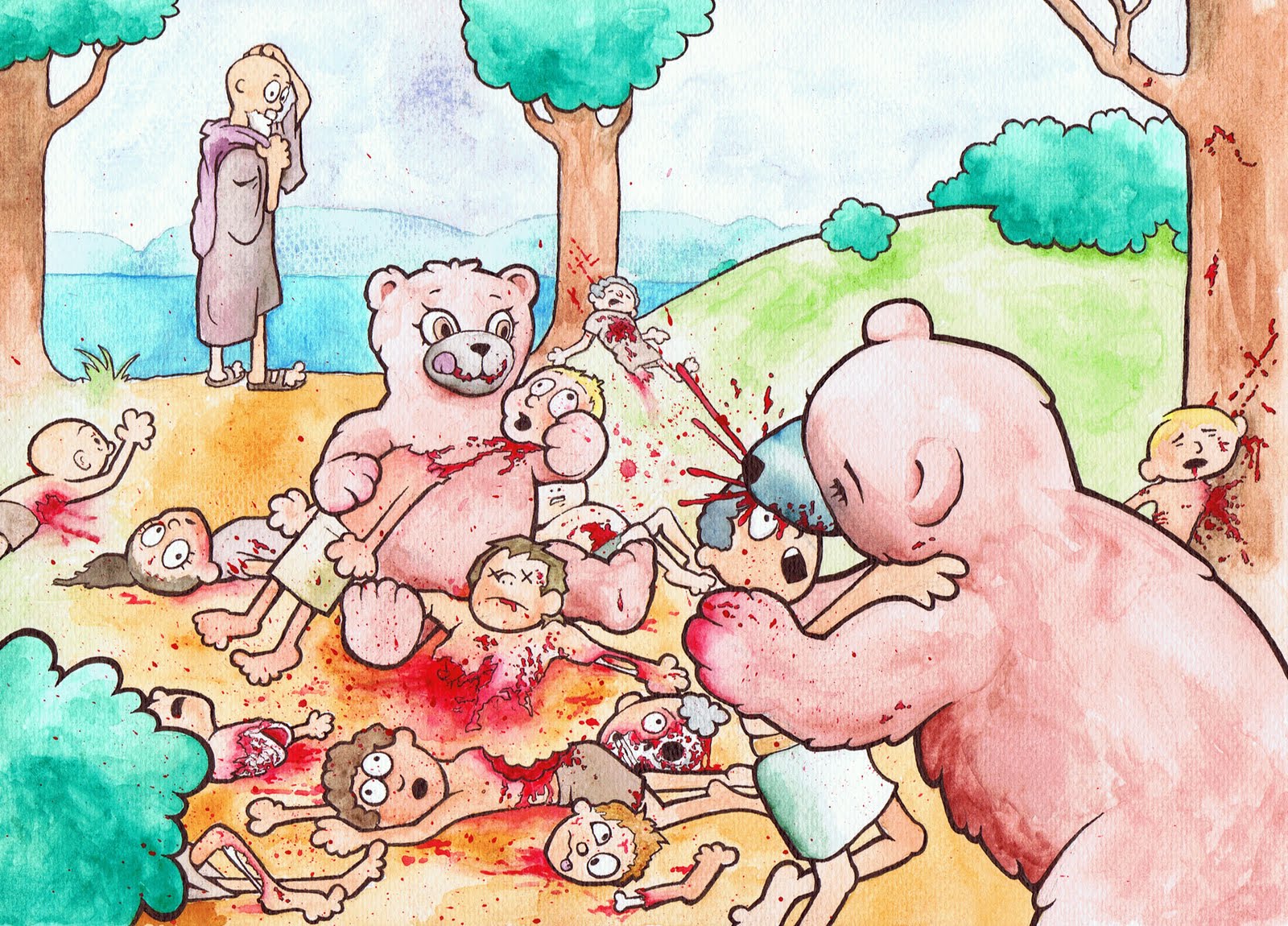

Elisha was one such prophet, and a story is recounted in Kings II, which pertains to the topic at hand. The waters of Jericho were unpleasant, and Elisha is called upon to heal them. He does so, and as he exits the city a group of children mock his baldness. Elisha curses these children, and two bears exit the nearby woods and eat forty-two children.

As with any myth (a term I use with reverence, not derision), the message is occluded through symbolism. The good myth is one which is able to withstand many different interpretations, and so although many before me have shared their interpretations of the Elisha myth, I will nevertheless attempt my own, which relies on a certain interpretation of blessings and curses that I must first explain.

Blessings and curses are spoken by Prophets. As a non-Prophet, I cannot say what powers lie within them and whether these actually cause changes in the world. But from my perspective, these verbalizations do not affect the cosmos, just as verbalizing the beauty of a sunset does not affect the sunset. What they do is provide a window into the mind of the Prophet. The Prophet is one who has a unique perspective and notices that which would otherwise go unnoticed. So as opposed to the verbalization of the beauty of a sunset, which is a tautology to anyone with eyes, the verbalization of a blessing or curse provides new insight.

Taken in this light, when Elisha curses the children of Jericho, he is not enchanting them with a mystical spell, but is rather pointing out a flaw in their character. The children have no sense of awe, and the prophet, who prevented their city’s destruction, is simply seen as an old bald man. The children are allowed to run free at the outskirts of the city and do as they please. One can imagine such children playing in the forest and encountering bears. They have no concept of danger, so they taunt the bears and laugh, with tragically fatal consequences.

I am afraid that ours is a culture of superficial children who lack the capability of perceiving depth. These days it is not Prophets who are forecasting our doom, but rather scientists. Whereas Prophets are upright moral characters who provide visions of the future as well as the motivation to work toward or away from it, scientists are simply conveyors of statistics. Human beings are not motivated by statistics, and no matter how many bar graphs one places in front of someone, his or her feelings about a deeply personal issue will largely remain unchanged. If the world is simply for our enjoyment, then why bother restraining ourselves? Only by looking beyond the human perspective may one learn to truly appreciate Nature, and without a true appreciation of Nature, its preservation is meaningless and its destruction inevitable.