Illustration by M Moore

__________________

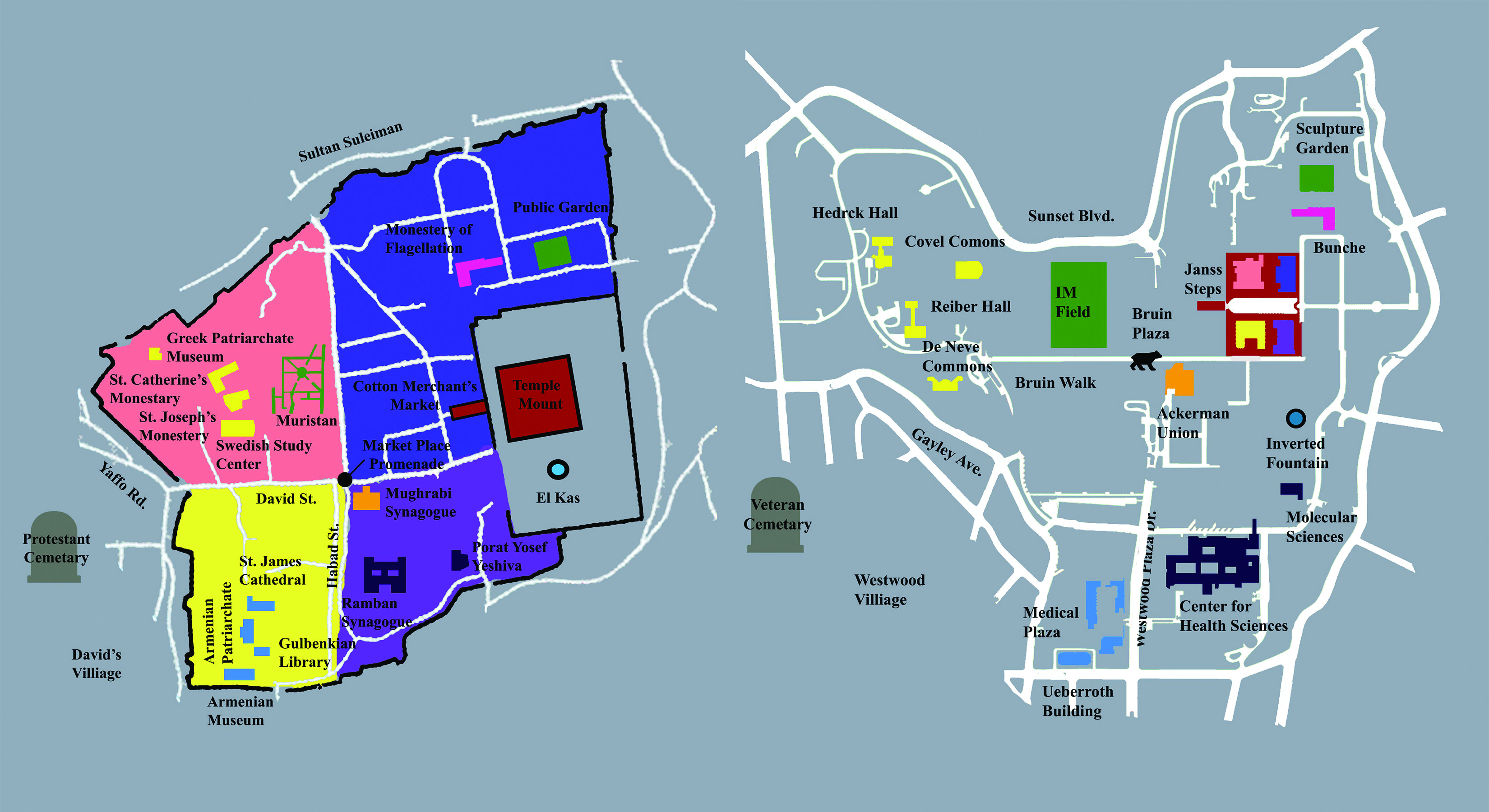

As I zoomed away from the ancient city, I noticed a freeway extending where the 405 would be. It was called the 50 freeway. “That’s not right,” I thought. I googled “50 freeway Israel,” and the internet provided what I was looking for. The 50 freeway was formerly called the 405 freeway. “That’s better,” I thought. As I continued on my trip, the stream of resemblance flowed unceasingly. The buildings and topography were the same. The parking lots, fountains and gardens all lined up. The four original buildings represented the four quarters architecturally. What I had been suspecting could no longer be denied: UCLA is based on the Old City of Jerusalem.

This observation of the eerie similarities between UCLA and Jerusalem came to me after I underwent double jaw surgery earlier this year. Since then, enough unusual occurrences have happened to make me consider writing a second sequel to Bruce Almighty, with myself played by Paul Rudd (or Woody Allen). The story recounted here is the least controversial and easiest of these occurrences to write about.

Upon my first day returning to school the Friday of the second week of the quarter, I attended a discussion for a class I was enrolled in: “Jerusalem: the Holy City.” The discussion began with an unexpected quiz on the topography of Jerusalem, which I learned of only at the beginning of class and crammed for before it was passed out. After class, I went up to the T.A., who had taught for a previous class I took, in order to discuss what I had missed in the two weeks I was recovering from my surgery. Before I could say anything about my absence, though, a thought struck me and I voiced it instantly: “Scott, the topography of Jerusalem looks a lot like UCLA’s.”

“Yes, it does,” he smiled. I bought the atlas required for the class and took a closer look at the map of the holy city as it looks today. It was only when I outlined it with the respective landmarks in UCLA that I saw how uncanny the similarity was. Of course, it had to be intentional, I thought. Everyone must have known. But after inquiring with professors, graduate students and rabbis, I learned that it was not so.

On the last day of class, when it was time for final questions, I nervously asked the professor from the top of the lecture auditorium if he could pull up a map of the city as it looks today. He did so and I asked the class if they noticed any similarities between that map and another one. At that moment, I got a phone call from a wrong number, and the opportunity passed with the professor quipping “George thinks UCLA is an imago mundi.” (I had mentioned it to him offhandedly in the past). As other questions followed, I saw fingers pointing to the projection on the screen as neighbors chattered and made their own comparisons. When I showed the professor the overlay after class, he too smiled. His reference to the term “imago mundi,” an “image of the world,” raises a good point. The city and its temple represented the Jewish conception of creation and the universe. At UCLA, the inhabitants, and not the buildings, make the school an imago mundi.

At UCLA, when I look around me I see an image of the world. We are privileged to study within an exceptional microcosm of the post-globalized age, in which the best of every nation is represented. Individuals of cultures that would be incompatible anywhere else form strong bonds and work together to better the world without a second thought. The old city of Jerusalem has four quarters: Muslim, Jewish, Christian and Armenian. The inhabitants of these quarters are, for the most part, rather isolated from one another. Here at UCLA, the Christian quarter and Armenian quarter parallel the dorms and Medical Plaza while the Muslim and Jewish quarters parallel the rest of the campus including the medical school. Here, our quarters have no borders. We mix and interact; we break the current global status quo. Our campus is a precursor to the city of the future.

But in spite of their similarities, these two spaces have considerable differences. A direct overlay of one on top of the other does not demonstrate much resemblance. Instead, although the buildings match in shape and formation, the quarters are warped in size from one map to the next. The section warped most dramatically is the Christian quarter, representing the dorms, in order to accommodate such a large student body. Just so, we, as the participants of this experiment in cohabitation, are learning to squeeze, stretch, and warp our various identities and ideologies to create harmony within our city. We are currently knee-deep in that process, to which anyone who is conscious of the recent tensions on campus can attest.

Is the architectural parallel between UCLA and Jerusalem intentional or unintentional? That is not important for us. What is important is what is happening here. Consciousness of this curious phenomenon is not required to be a part of it. It does, however, allow us to be grateful for it, and that is a blessing in and of itself.