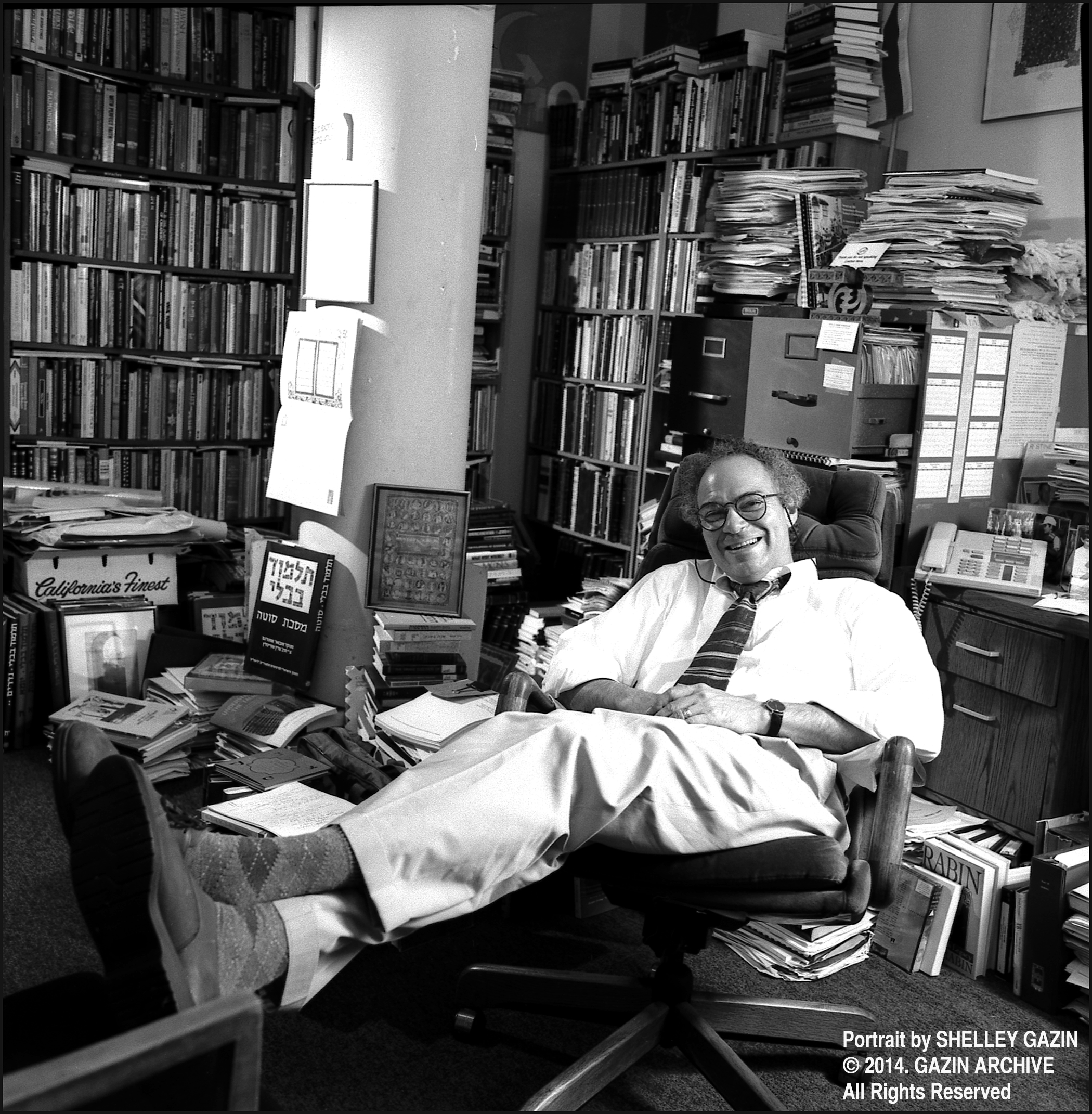

Portrait of Rabbi Chaim Seidler-Feller in his Hillel office at URC, a selection from “Looking for a Rabbi: Photographs by Shelley Gazin, 1999-2001.” (Copyright 2015. Shelley Gazin. All Rights Reserved.)

_______________

Some would start a farewell address to Rabbi Chaim in this fashion: “Rabbi Chaim Seidler-Feller will be retiring this year from his position as Executive Director of the Hillel. As an educator, his greatest achievement lies in the countless students he has taught and inspired. Although he will no longer be present in an authoritative capacity, his impact on our campus will be felt for many years to come. Over his illustrious 40-year career, Rabbi Chaim has overseen the development of a vast network of programs for Jews of all backgrounds. The continuity of these activities is ensured because they have a home in the Yitzchak Rabin Hillel Center — also of his doing. This building sits off the edge of campus but serves as the epicenter of Jewish life here.”

But I know Chaim (he prefers to be called by his first name), and this style doesn’t suit him. Not that any of it is untrue — if anything, it is an understatement. But it’s far too neat to convey Chaim’s unique personality, which is what our campus will sorely miss with his retirement. On the door to Chaim’s office is a quote from Einstein: “If a cluttered desk is a sign of a cluttered mind, of what, then, is an empty desk a sign?” To give a sense of what clutters his mind: Chaim’s desk is mostly covered with books.

Chaim attributes the survival of Rabbinic Judaism even after the destruction of the temple to the fact that we created a portable temple in the form of the books we wrote. Yet, the way Chaim surrounds himself with books, he creates a not-so-portable temple, after all. If those who built the Tower of Babel sinned for stacking their bricks in an attempt to challenge G-d, Chaim sins for stacking his books ever higher in an attempt to understand G-d’s creation.

Books are important to Chaim not only as a means of transmitting knowledge, but also as conduits to the past. For instance, on Passover, Chaim not only commemorates the Exodus itself, but also the various ways in which Jews have commemorated the Exodus throughout the ages — as one of his most prized possessions is his vast haggadah collection, which includes some beautiful, old manuscripts.

But books are not the only source through which Chaim connects with our nation’s rich history. Chaim collects relics from all aspects of Jewish life, most of which are on display in his house, a museum-of-sorts. These artifacts have been salvaged from all over the world, and Chaim serves as their curator. The easiest way to excite Chaim is to ask him to talk about them; he has an explanation for what each item is and how he came to acquire it.

Sometimes acquiring them even takes precedence over teaching. One time Chaim answered a phone call which had interrupted our class. We figured it must have been an urgent matter, and later laughed when we learned that the person on the other end was at an auction, purchasing a book for Chaim.

But most of the time, teaching takes precedence over everything else, something I was reminded of just the other day. We had made an appointment and as I sat down at the designated time, the assistant from the front desk notified Chaim that a reporter from the Daily Bruin was calling him to ask about Zionism. To explain a complex notion such as Zionism to someone who has little experience with it is a difficult task, but this is the task of the educator — and it is something Chaim has dedicated his life to doing.

Chaim’s mind was at work trying to consolidate all his information on the subject into a concise presentation. His monotonous tone was punctuated by a slight stutter, as the engine of his mind was revving. I like to think of his stutter as the consequence of the impossible task of containing his vast knowledge into limited ideas and words.

As the phone call went on, he continuously extrapolated on his previous statements, getting more enthusiastic as the threads of ideas spiraled out into a magnificently patterned web. He had worked himself into an intellectual frenzy — his usual demeanor when teaching, reflected in the whimsy of his tone and the wiggling of his hands. His whole body is wrapped up in his teaching; if he starts delivering his talk while sitting, at the peak of his excitement, he stands up, and if he starts while standing, then he ends up pacing.

While the mannerisms accompanying his teaching are his own personal style, the structure of his teaching is firmly rooted in rabbinic tradition. Just as the Talmud unpacks the pithy statements of the Mishnah, Chaim provides a source sheet with excerpts from various texts spanning the ages. He interprets the texts and weaves them together, expanding on the statements and ideas of others, going off on tangents and telling anecdotes that all play into one another, for as long as you will listen to him, and then some.

Learning with Chaim is like watching an interpretive performance, but it is not a solo act. As Chaim drifts away further and further into the realm of ideas, he reaches out to the audience to make sure they are fellow travelers and not passive observers. He asks questions and even extends his arms, tapping those sitting next to him. When Chaim learns, he must be assured that you are learning too.

In the middle of his call with the Daily Bruin journalist, his cell phone rang and Hillel’s upcoming Executive Director, Rabbi Lerner, entered his office. Although all of these people were vying for his attention, what was most important to Chaim in that instant was making sure that he had taught the potential pupil on the other end of the phone. But his dedication to this stranger was not confined to that one phone call. A few hours later, I discovered him back on the phone with the reporter, presenting a simplified formulation of Zionism which he felt would better suit her, giving her his personal number in case she had more questions.

Although Chaim’s ultimate passion is teaching — and he relishes every moment he gets — it’s become a less frequent pleasure these days, as he made the tough decision in 1996 to focus his energies on fundraising. This fundraising has enabled the construction and maintenance of the magnificent edifice on Hilgard Avenue, which reflects both Chaim’s personality and his vision of Judaism. The design of the building is purposeful, and small subtle symbols pervade the building.

For example, alongside the front doors stretches a thin banner of repeating Hebrew words etched into the glass. Upon entering, it reads ‘and you should teach them’; upon exiting, it reads ‘and you should love.’ While in the building, our primary injunction is to learn Torah, everything else is commentary.

This is mostly overlooked by students, for which the building serves primarily as a center of some combination of the following activities: food, community, culture, religion, and service. In Chaim’s ideal form of Judaism, all of these various aspects of life must be balanced, for they enrich one another — but ultimately, Torah must be their source.

Chaim anticipated that housing Jewish students of all denominations under one roof would lead to mingling between the different groups and the emergence of a vibrant Jewish atmosphere. However, this vision is predicated on all students being equally interested in learning and debating Jewish principles — which is unfortunately not the reality. Thus, although Hillel fosters a great amount of Jewish social engagement, Chaim’s vision of our community has yet to be fulfilled.

The lack of trans-denominational Torah study does not only limit our ability to argue and learn from other Jews, but also diminishes our confidence when confronting external challenges to our Jewish identities. Perhaps we, the active Jewish students, have a difficult time carrying the ideals of the Hillel center with us across campus because we are ignoring our greatest asset in shaping and empowering our Jewish identity: our portable tradition which we acquire through study.

To some extent, Chaim’s emphasis on studying Torah is a holdover of his youth, which was spent mostly at yeshivah. He is heavily rooted in the rationalist tradition he was born into. A quote from Maimonides is inscribed on the underside of his watch: “For the intellect is the glory of G-d.” While most wear a watch to keep track of time, Chaim — who has little use in keeping track of time — utilizes it to keep aware of the supremacy of the mind. This quote serves as a reminder both to himself and to those around him, as he frequently removes his watch in the middle of teaching a class to read it.

However, he has diverged radically from the yeshivah world, and uses his knowledge to subversively undermine it. Whereas each yeshivah usually designates a realm of Jewish thought, such as mysticism or philosophy, as heretical and therefore too dangerous to study, Chaim adheres to no such limits. G-d is glorified ever more greatly when the intellect is applied to all avenues of thought.

Chaim is quick to admit himself that he did not create ex nihilo this approach to Judaism. If he can see far, it is because he stands on the shoulders of Gedolim (giants of Jewish thought): Moses, Maimonides, Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik, Rabbi David Hartman. Each of these men fought subversively against the ideological institutions that surrounded them: Paganism, Islam, Modernity, and Orthodox Judaism, respectively. Rabbi Chaim fuses all of their struggles into one unceasing metaphysical battle.

Chaim views life as a constant dialectic struggle between competing forces, in which it is up to the individual to make decisions at every moment; since Chaim’s mind is constantly at war, an aura of urgency pervades him. His mentality and mannerisms, transplanted from New York, often look out of place here in sunny Southern California. But bundled with this combative persona is a warmth and a sense of humor. The seriousness of life and the self-importance that results from its awareness is always kept in check by self-reflection, community, and G-d. These forces are a constant reminder of the limitations of the individual and the inevitability of error.

Chaim recently told me that, as a result of new readings, he feels compelled to reconsider certain aspects of the historicity of the Exodus. Not many people, especially of his age, are able to change their minds about anything, let alone something of such seeming importance. For Chaim, the answer isn’t as important as the question: you must have answers, but you must also always keep the questions open for revision.

Chaim’s goal has been to empower young Jewish students to grapple with the many questions Jews are faced with, as individuals and as a community — not to answer the questions for you, but to make sure that you are aware of the questions. As a result, Chaim has students who have gone on to become rabbis in every denomination of Judaism. For some this would be a source of mourning, but for Chaim, it is a source of pride. Perhaps the reason many Jews don’t learn Torah is because there aren’t many like Chaim who are able to learn and teach Torah in a way that is palatable to Jews of all backgrounds.

I suspect that as Chaim leaves his role as Hillel’s Executive Director, he will find that he has more time to do what he loves most: educating and empowering young inquisitive Jewish minds. Rabbi Chaim serves as an endless source of inspiration to me, and I hope he will be able to spread his wisdom to many more searching souls. To many more healthy years full of tensions and questions and vibrancy: L’Chaim, to Life!

__________________________

Culminating thoughts from Rabbi Chaim:

“I came to UCLA excited by the possibility of engaging with students who were searching for meaning and who were looking for an opportunity to discuss life’s dilemmas and the fundamentals of Judaism. I was especially interested in those who wanted to challenge the basic assumptions of the tradition. Here I felt that I could guide young Jews in an attempt at forging a worldview that generated a significant encounter between tradition and modernity. Forty years later, that’s still what animates and inspires me.”

__________________________________________

Photo by Jonathan Jacoby, Ha’Am October 28, 1975

Photo by Jonathan Jacoby, Ha’Am October 28, 1975

FULL CIRCLE: Rabbi Chaim Seidler-Feller was first profiled by Jonathan Jacoby in Ha’Am’s October 28, 1975 issue (above). Forty years later, Ha’Am has the pleasure of chronicling Rabbi Chaim’s final words to the UCLA Jewish community.