A glance at the iTunes digital bookstore’s

Politics and Social Sciences category may prompt a double take. Among political

journalism dynamos such as Charles Krauthammer, Mark Leibovich and Lou Dobbs, another

familiar name seems incongruous — Adolf Hitler.

Mein Kampf, the anti-Semitic

diatribe written during a period of incarceration by one of the most notorious

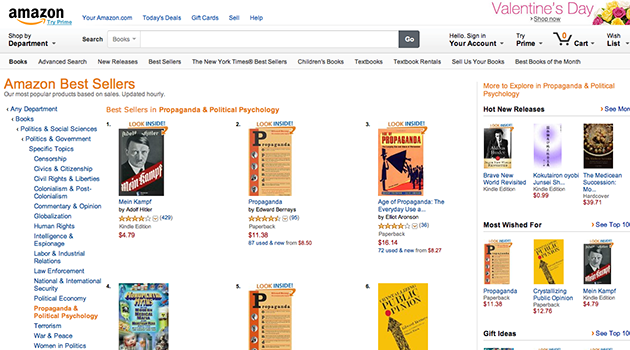

men in history, sits proudly at the third spot. In Amazon’s Kindle bookstore, Mein Kampf has earned top honors within

the “Propaganda & Political Psychology” subcategory.

The manifesto’s rise to bestseller status at the beginning of 2014 is surreptitious and startling, far different from the drama-riddled ascent of its author almost a century earlier. Imprisoned for a failed coup in 1923, Hitler channeled his frustrations and unexpected free time into a painstaking description of the Jews’ aspirations to achieve world domination and the actions that must be taken to prevent it. The resulting tome not only became his de facto political platform, it also proved to be an absolute cash cow and a powerful indoctrination and recruitment mechanism that worked like magic on Germany’s young adults.

Why the sudden revival of Adolf Hitler’s literary incarnation? Time Magazine’s Kyle Chayka points to Chris Faraone’s explanation “that argues e-books provide the perfect format for reading controversial material.” Chayka labels Faraone’s idea “the 50 Shades of Grey effect” — while a consumer may be reluctant to admit interest in risqué or taboo material by exhibiting hardcopies on a shelf, an e-reader affords an unprecedented level of privacy by concealing titles, authors and content within megabytes of electronically encoded data on a microchip. One can easily visualize a houseguest perusing a large bookshelf in the living room during a dinner party, but it is hardly acceptable to parade into a host’s bedroom and snoop around in his or her Kindle.

In addition, the purchase of books in electronic form has become as anonymous as their storage — no need to confront the prying eyes of fellow shoppers or the judgmental raised eyebrows of a cashier. Reading is now a private activity — a click of the mouse is all it takes to transfer the text instantaneously from a password protected bookstore account to a personal e-reader. Before the advent of Kindles and Nooks, to whip out socially offensive literature in a public place was hardly fathomable. Today, however, we have no idea what the fellow sitting across from us at the coffee shop is reading — for all we know, it could be Mein Kampf.

Faraone posits that the recent popularity of Hitler’s history-jolting work can be summed up by the following Amazon customer’s comment: “I think I waited 45 years to read Hitler’s words…I wish I had read it sooner.” Faraone also divulges that Elite Minds (who recently released an e-book version of Mein Kampf) President Michael Ford has “not heavily promoted the book and decided, for the most part, to let it spread among those who have a true historical and academic interest naturally.” In other words, the general consensus seems to be that Mein Kamp’s high ranking has resulted from socially-conscious historians and academicians flocking to the e-book marketplace in droves, finally given the opportunity to make a clandestine purchase of Hitler’s doctrine.

By this logic, the obvious concerns over the widespread dissemination of genocidal literature should be assuaged by the knowledge that it is being examined solely as a document of historical significance. As would be expected, many Jewish groups have not been blissfully comforted by such an innocent explanation.

Fox News reports that Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, agrees with Faraone that the “anonymity provided by e-books has ‘absolutely’ been a factor, particularly in Germany.” However, he does not see the phenomenon as an innocuous outpouring of pure academic curiosity — indeed, data supports the claim that college history professors do not make up the majority of new readership. Chris Faraone writes that “trying to curb Hitler’s sales has proven a futile exercise worldwide. Since showing up in Asia 15 years ago, ‘Mein Kampf’ has sold in excess of 100,000 copies in India. In 2005, the debut of the first-ever Turkish translation sold 100,000 copies in the first two months. And now, with the e-book revolution in full swing, readers are downloading Hitler everywhere.”

Rabbi Cooper also claims that Mein Kampf was “also distributed last year by North Korean ruler Kim Jong-Un to his top officials as a leadership skills manual. Kim reportedly handed out translations of the text during his birthday in January, according to a report by New Focus International, an online outlet operated by North Korean defectors.”

Smartly avoiding the topic of banning the book altogether (which would violate freedom of speech and would likely only increase the book’s popularity), Rabbi Cooper reportedly believes that “annotating it is a thoughtful compromise that would help new generations of readers properly understand a book [that] continues to propel ‘very disturbing, very corrosive’ views of Jews worldwide.”

To

this end, the Anti-Defamation League offers an introduction crafted by

Holocaust survivor and ADL National Director Abraham Foxman that serves to

ground Mein Kampf in its historical

context. Rabbi Cooper does not hold out much hope that similar introductions

will become compulsory additions to digital copies of Mein Kampf, but without a qualifying disclaimer, the

genocide-friendly text may be misinterpreted and can be used to further

sinister objectives. As the distribution of Hitler’s ideas is becoming less

verboten, we must quickly find a way to ensure that the ideas themselves remain

untouchable. If Mein Kampf becomes

bedtime reading, we may gradually blunt the pain its horrors have caused and thus,

we may give history a chance to repeat itself.