Last week, I visited the Israeli consulate to renew my passport. As the lady at the desk was happily typing my information into her computer, a sense of relief quietly overcame me, knowing I would soon be one step closer to being home again after nearly a decade. The playback of a tearful Hollywood family reunion at Ben Gurion Airport came to an immediate halt, however, when I noticed her fingers stop and her face grow concerned.

She dials a number on the phone, looks to me and asks, “You were born in ‘93?”

I quickly reply, “Yeah, why? What does that have to do with anything?”

She nods and turns back to the computer as a voice picks up on the other line. The voice gives instructions and she begins typing again. She nods her head, every few seconds opening up a manila folder with numbers I can’t make out. She thanks the person and hangs up the phone.

“Okay, you’re already 21. So before I can renew your passport I have to get a confirmation from the IDF offices that you no longer have to—”

“It’s already taken care of, didn’t you read that paper in my passport? I got an exemption for another year or so.”

“Maybe if you let me finish,” she gives a smile filled with apathetic sarcasm and I shut up. For once my Israeli arrogance is not offensive, just reciprocated. “You’re 21 and a female. You won’t have to be drafted to the army anymore.”

“Wait what? I thought it was… Are you sure? “

“Yeah, some … changes happened.” She purses her lips, “You’ll be cleared once they get back to me.”

After a little research, I learned that in fact, as a child of immigrants and a female who reached 21, I won’t need to keep pushing back the call to service that’s been waiting for me since I was 16. I’m simply free from it.

As I leave the building that day and every day since (waiting for a long line of bureaucracy to grant back my little blue book), that fact sinks in. I, a born-and-raised Israeli, will never serve in the army. I should be happy, right? I’ll never have to endure the sleepless nights, the awful food, the cleaning duties, or the Saturdays on the base. “Anyhow,” I rationalize, “I’m in college. By the time I get my bachelor’s, and master’s, then doctorate… who has time for a two-year-long full-time job I can’t put on a resume?”

Eventually, the thoughts swirling in my head formed a sinking sense of loss, one I never considered before.

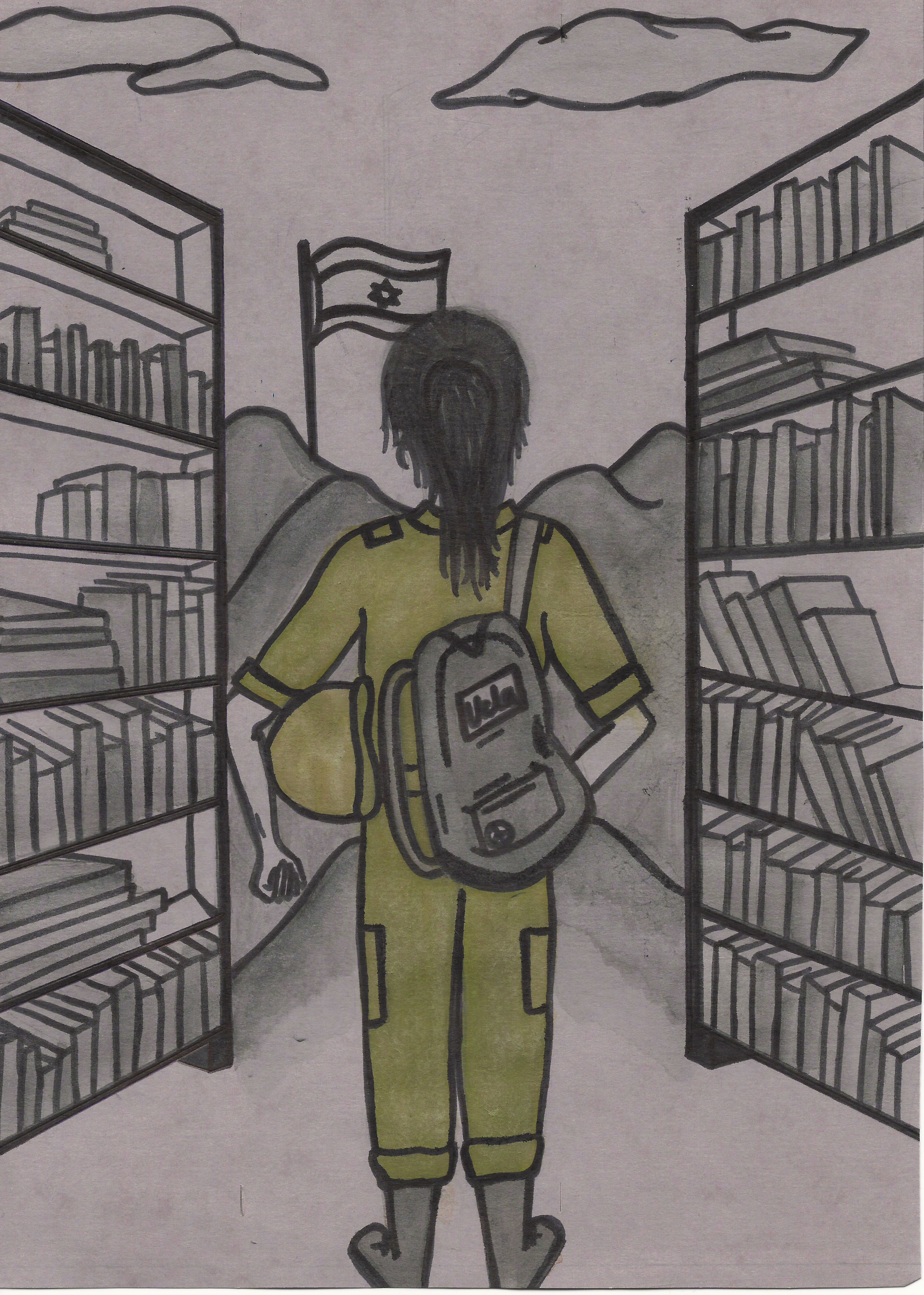

I won’t report to the BAKUM with mom and dad as they half-heartedly send me off, telling me what it was like when they were my age. I won’t know the bond between unit members. I won’t salute and pay respects to those who have been keeping my family and people safe. I won’t learn military discipline, or be liable for others’ triumphs and failures. I won’t have my 21-year-old-arrogance spat back at me, my will broken and reshaped in the Zionist vision. And I’ll never wear that uniform – that same olive green my grandfather wore in every war from ‘56 to ‘73. The green my uncles have been wearing since being drafted in the ‘70s. The green my father wore in Lebanon in 1982. The green my cousins and childhood friends are wearing as I write this, sipping a soy chai in my cozy Los Angeles apartment on a Saturday afternoon.

That olive green uniform has been passed down in my family for three generations, and I’m the exception. Suddenly, my ten-year plan seems distant, less than perfect. I’ve spent the last years of my life chasing American dreams and lost sight of my Israeli, my Jewish, my familial obligations.

Meanwhile, there are Sarvanim (or in English, Refusniks) who live in Israel refusing to serve. To each his or her reason – religious, political, personal – and whether they are acceptable or not is up to the IDF to decide. I, too, have my convictions about the military’s place in Palestinian territories, but is it my place to decide? Like every Israeli, I have the harshest criticisms for my country, but do they absolve me from serving for it? Is my privilege of not having to serve a blessing or a curse?

In an intimate screening of Beneath the Helmet, a coming-of-age film about the transition of five Israelis from high school and into the army, some of my confusion was alleviated on one hand, but on the other, the sense of duty owed to my country deepened.

The interactions and bonds between soldiers, commanders and the meaning of their service are colored with the many backgrounds of each, some moving from the other ends of the world to live and serve in what they call their “homeland.” All of them, united by a life-and-death duty to the Jewish heritage, feel that they are serving themselves and history in the best way possible, wearing that olive green uniform. Private Oren Giladi, a lone soldier, is seen visiting his family in his home overlooking a breathtaking Swiss mountain landscape. He recounts thoughts he had before packing up and leaving for the IDF: “Switzerland doesn’t need me. Israel does.”

At the end of the screening, we heard from Lt. Aviv Regev, who came to speak on the film and is an Israel advocator. “You don’t need a uniform to defend Israel,” he said. We all have the power, and duty, to defend Israel, and we can do it right here on campus. As Jews, we have the duty to challenge the voices against Israel. It’s not enough to be Jewish and proud, or even attending pro-Israel clubs and events.

To defend Israel, we must find the courage to stand up to the lies and ignorance. To be able to do so intelligibly, we must be educated and ready to respectfully and emphatically respond to questions and concerns of others about Israel and the Middle East. Take a class about the topics interesting to you, go to talks, or read up on the quick and easy fact sheets offered by StandWithUs.

As for me, enlisting in the IDF or keeping my ten-year plan is yet another conflict that will be tackled in the years to come. While our soldiers keep our home safe, the fight for Israel is worldwide, and as Jews and Israel advocates, we are at the front of the line.