Two weeks ago I wrote an article about Jerusalem, its vibrant energy, and the stubborn distance between its different groups. I ended with a suggestion, a hope, and a recycled Lennon lyric: let us recognize that despite the differences, we are all the same.

“You may say I’m a dreamer.” Maybe coming together despite the enormous, irreparable pain caused by our conflicting differences is blindly naïve — so blindly naïve that I must be so far removed from the situation to even verbalize such a simple utterance with any shred of hope that it resonates with anyone.

“But I’m not the only one.” Many share this dream, and the most important are those living in the midst of a reality that begs and aches for the dreaming.

The stubborn distance stems not merely from the theological premises of the Jewish, Muslim and Christian faiths, but their relationships to Jerusalem. It seems the fact all three find their high place of worship in the same location is not a possible point of unity, but rather the beginning of separation. Between the faiths, and especially within Judaism, the conflict lies in “to whom does Jerusalem belong?”

There is a never-ending struggle for Jerusalem’s image between the groups. Each claims its vision is the only one, or the only right one, and all the rest are the “other.” It seems that in claiming one’s relationship to the city, one necessarily must deny all other claims to it.

This past Sunday, The Y&S Nazarian Center for Israel Studies at UCLA hosted a conference called “Israel in 3D 2015, Spotlight: Jerusalem.” The array of presenters walked us through the re-imagination of a new city on old grounds.

The conference began with Meir Kraus, Director General of the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. He asked us to imagine each group having its own special relationship with Jerusalem, while simultaneously working together toward a single, sustainable city.

It ended with Israeli Minister Dan Meridor. He said the problems of Jerusalem are of massive dimensions, recognizing that the ability to chip away at the bigger issues is not in the the mayor’s hands but in the knesset’s. Jerusalem has been historically considered the last unsolvable component in a potential Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement.

As is, Jerusalem is a stumbling block in the peace process. But in our little big dream, it is the point of resolution. Perhaps politicians are lost as to how to approach the tension because the resolve to do so lies in the hands of the people themselves.

Many of the panelists presented their own way of chipping away the tension from the ground up. These civil initiatives are unique, each targeting a small yet integral piece of the larger issue. I was especially inspired by a few:

Tehila Nachlon co-founded Yeru-Shalem, a coalition of organizations working together for an inclusive Jerusalem. Though she is Orthodox, she took personal initiative by organizing various outdoor activities in response to Unorthodox Jewish families feeling ostracized on Shabbat. She said although many of the activities are legally considered a desecration of Shabbat, she sees her work as helping others, which she considers to be more important.

Rebecca Bardach and Mohamad Marzouk are directors of “Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education in Israel.” Together they opened up a public, state funded school that offers both Arabic and Hebrew tracks so that Jewish and Arab children can learn and play side by side.

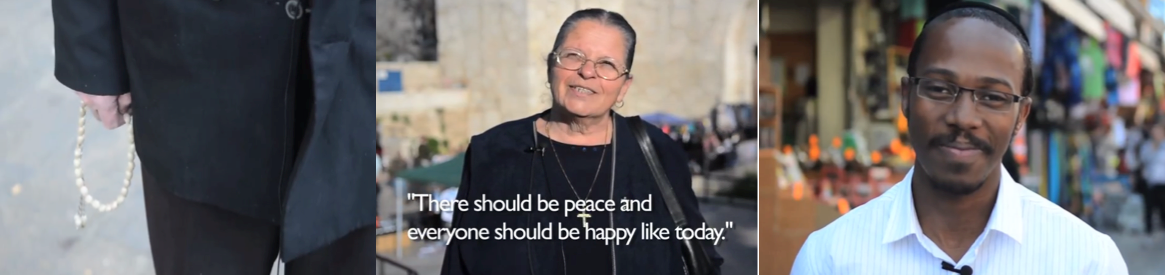

Joseph Shamash and his team created the “One Wish Project,” a traveling documentary asking people one simple question: What is your one wish? Next year they will be traveling to Europe and Israel to document an international dialogue about anti-Semitism.

I find the One Wish Jerusalem video fitting in telling this story, as it invites us into the realities of everyday life in the city. It shows the complexity birthed from the different identities, putting faces on the claims that divide and “other-ize.” But in equal proportions, it puts faces on the dreams. What politicians see as far-fetched ideologies are the hopes of real people, manifested in their dialogue on (and off) camera. If Jerusalemites are able to dream and wish for peace, who are we not to?