As the exuberance of yet another AIPAC Policy Conference fades, the grimness of reality sets in. This year’s AIPAC conference featured such speakers as Vice President Joe Biden and outgoing Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak. But while this week’s headlines highlighted these superstar speakers affirming and reaffirming the unshakeable U.S.-Israel alliance, this week also saw the passing of one of the most adamant proponents of the peace process. On Monday morning, Rabbi Menachem Froman, the longtime resident of the West Bank settlement of Tekoa, succumbed to his three-year battle with cancer.

As the exuberance of yet another AIPAC Policy Conference fades, the grimness of reality sets in. This year’s AIPAC conference featured such speakers as Vice President Joe Biden and outgoing Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak. But while this week’s headlines highlighted these superstar speakers affirming and reaffirming the unshakeable U.S.-Israel alliance, this week also saw the passing of one of the most adamant proponents of the peace process. On Monday morning, Rabbi Menachem Froman, the longtime resident of the West Bank settlement of Tekoa, succumbed to his three-year battle with cancer.

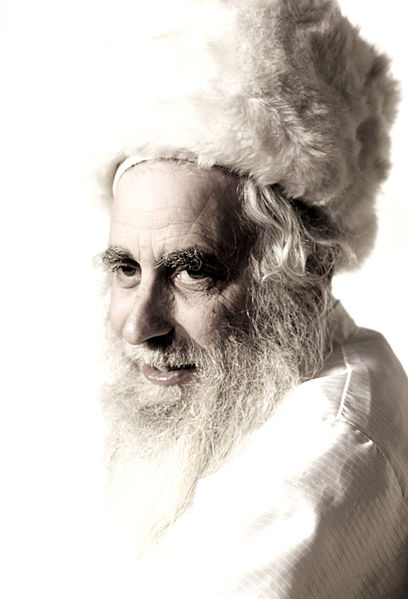

As the former chief Rabbi of the Knesset and a religious leader in the settler movement, Froman appeared as an anomaly on the peace process landscape. He bore none of the characteristics commonly associated with peace advocates, possessing no foreign policy expertise and membership in the right-wing settler movement. However, more important to Rabbi Froman than the political dogmas of his community was his belief that peace is preferable to war and life preferable to death, regardless of the loyalties of those involved. Through the promotion of interfaith dialogue, Froman advocated for a lasting peace between Palestinians and Israelis through the recognition the shared values and points of mutual agreement among religious groups.

He was widely criticized for frequenting the offices of former Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat and of Hamas founder Sheikh Ahmed Yassin. He even negotiated terms for a lasting ceasefire with Hamas (termed the Froman-Amaryah agreement) against the urging of the Israeli government. Froman contacted journalist Khaled Amaryeh in 2008, and together, they developed a comprehensive plan in which economic restrictions would be lifted off of Gaza in exchange for an end to Hamas’s rocketing of Israeli towns. Froman was an ardent critic of the Israeli government’s reticence to pursue dialogue with different Palestinian factions. As he openly expressed, refusal to negotiate with neighboring adversaries was a product of American hubris — a luxury that Israel could not afford.

Rabbi Froman’s greatest strengths lay not in his desire to engage with those deemed dangerous and uncompromising, anti-Semitic and hostile, but in his capacity to render all conventional wisdom and stereotypes moot. In an era in which politics have grown increasingly polarized, Froman’s work proved the tendency to over-simplify Israel’s position in the Middle East — often portrayed in terms of “good” and “evil” — obsolete.

Judaism reserves a special term for those like Rabbi Froman — a rodef shalom — literally, an active pursuer of peace. In the Jewish Haggadic text “Avot of Rabbi Natan,” the act of pursuing peace is held up as tantamount to fulfilling the entire Torah. While Froman’s politics might not resonate with all of us, he leaves a legacy in which all of us can partake. His proactive approach and and willingness to challenge conventions and norms represents a paradigm scarcely seen in Middle East politics. The direction of the peace process remains uncertain; with hostile posturing from Iran and unrest in Syria, it seems unlikely that any significant breakthrough will arise in the near term. Nevertheless, we can hope that Rabbi Froman’s message to pursue peace, even in the most unconventional of ways, will be heeded by those who strive for peace in Israel’s future.