One of the many beauties of studying Torah is tracing an idea to its origins thousands of years ago and seeing its final effect in our society. This week’s parshah (Torah portion), Mishpatim, opens with the laws of treatment of Hebrew slaves. The first law in our parshah is that after six years of work, a slave is set free, for he has no real master except for God. At this point, we must take a step back and wonder: What is the Torah telling us in regards to the overall morality of keeping slaves? As many have learned, this is not a very simple debate and opinions range from one extreme to the other; however, I would like to present what I think is the correct reading on this subject.

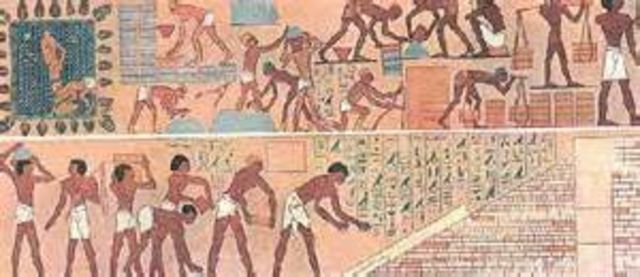

In Biblical times, having a slave was basically the modern day equivalent as owning a computer. Firstly, a slave was considered nothing but property, and secondly, the use of slaves was seen as the only realistic way to run any type of business. In this light, when we see the Torah and its limits on slave ownership, such as freedom after six years, the decree against working your slave on Shabbat, or the many laws against beating or harshly treating your slave, we must recognize the moral progressiveness of these enactments. However, even with all of these progressive laws, owning slaves was still seen as a normal and completely moral and ethical to run a household or business.

During the Talmudic age, the rabbis, obviously feeling that even the laws of slavery in the Torah were not enough, enacted many new progressive laws, all with the intention of protecting slaves. Some of the laws enacted in the Talmud are that a master must make sure his slave eats before he does; if a master only has one bed it goes to the slave; and many other laws ensuring the wellbeing of a slave during his years of slavery. The Talmud made it so difficult to take care of a slave that a famous comment in the Talmud states that “whomever acquires a Hebrew slave acquires a master” (Kiddushin 20a).

In the middle ages, it was very rare for Jews to own slaves. Maimonides, the famous 12th-century philosopher, never actually commented on the ethics and morals of slavery, but we can infer what his probable opinion on the matter would be. The way that Maimonides viewed many of the laws in the Torah, such as all animal sacrifices, was that the only reason why the Torah commanded these laws in the first place was because it was necessary in the ancient society in which the Torah was given. According to him, having sacrifices was never a Jewish ideal; however since the idea of monotheism and one non-physical God was already a huge jump in theology at the time, the people at least needed animal sacrifices to be somewhat like the surrounding nations (Guide for the Perplexed 3:32). In this light, we can imagine that Maimonides would have had a similar opinion regarding slavery. In Biblical times, since it was inconceivable for any society to exist without slaves, the Torah, instead of ideally abolishing it, created many laws which over time would slowly wean the Jewish people from the need to own slaves. This is the opinion of many prominent rabbis, including Rabbi Nahum Rabinovitch, one of the leading Torah scholars of our generation.

Taking this idea a step further, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi of the British Empire, provides a deeper explanation. Instead of conspiring to the idea that Torah merely made it very difficult to own slaves, his opinion is that the Torah in its entirety is one giant polemic against the idea of slavery. The basic story of the Torah is that God saved a nation of slaves (the Jews) from Egypt, and lead them into their own land, giving them food and shelter along the way. Time and time again, the Torah tells the Jewish people that they must be nice to the stranger, the slave and the orphan — for they were once “slaves” in a foreign land. In this light, we can argue that although the Torah does write laws about owning slaves, it also writes laws about how to repay stolen objects, divorce a spouse or leave for war — matters which were not progressively dealt with at that time in society.

As we read Parshat Mishpatim this week in synagogue and encounter many ideas which perhaps seem archaic and against our moral intuition, we must see the larger sociological and spiritual context. We must understand how these laws have actually helped create the morally progressive and ethical society that we find ourselves in today.

Shabbat Shalom!

—

This article is part of Ha’Am’s Friday Taste of Torah column. Each week, a different UCLA community member will contribute some words of Jewish wisdom in preparation for Shabbat.