The Titanic of Today

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902-1994) of righteous memory, the Lubavitcher Rebbe and the seventh and last leader in the Chabad-Lubavitch dynasty, never visited Israel. He also never gave a definitive reason as to why. Legend has it, he was concerned: had he traveled to the Holy Land, its holiness would have prevented him from returning to the Hassidim who needed him. Once, when asked why he did not travel to Israel, the Rebbe answered, “When the ship is sinking, the captain has to put all of its passengers on the lifeboat first. Only then is he allowed to jump in himself.” He explained that the world Jewry is the sinking ship and Israel is the lifeboat.

—

The holiest of holies is the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel. It is the location of the bedrock known as “The Foundation Stone” (Even ha’Shetiyah), where, according to ancient sages, God founded the world on the first day of Creation. The prophet Isaiah stated, “The Lord God said: ‘Behold, I have laid as a foundation a stone in Zion, a fortress stone, a costly cornerstone, a foundation well founded'”(Isaiah 28:16). This bedrock became the pivotal center of the Holy Temple (Beit Ha’Mikdash) built by King Solomon in 832 B.C.E., according to the Hebrew Bible and the 2nd-century C.E. Hebrew language chronology. Eventually, the First Temple would be destroyed and the Second Temple as well.

Withstanding centuries of conflict and colonialism, the only architectural remnant of the Temple is the Western Wall (HaKotel HaMa’aravi), the protective perimeter of the Temple platform, built by King Herod in 19th-century B.C.E. In a momentous victory of Jewish history and by the State of Israel, Jews reclaimed the Western Wall during the Six-Day War in 1967.

Today, the wall spans a total length of 588 meters, but only 57 meters are exposed in an area known as the Western Wall Plaza, commonly referred to simply as the Western Wall or the Wailing Wall, where people come to pray. Since rabbis forbid praying at the holy Temple Mount, the Western Wall has instead become the epicenter of prayer for an untold number of individuals spanning millennia.

Following a rich but regretful history of war and religious conflict, the Western Wall is thus not only a place of beauty, but also one of sensitivity. People from all walks of life travel to this site to pray, to leave a note in its cracks, and/or to preserve the momentous visit in a photograph. Many are overcome with emotions, once tucked deep in their psyche, or perhaps, if I dare say, soul. The experience of being where the legacy of Jewish ancestry can be seen, touched, and felt is truly beyond words.

However, the Western Wall’s beauty is also scarred with a sandstorm of sadness and madness. In a sense, many are fighting and the Western Wall is wailing. This past month, the State of Israel initiated a nine-million-dollar plan to expand the Western Wall by the southern side, near Robinson’s Arch, an unused archaeological site. This nine-meter expansion would provide a permanent mixed-gender space. Currently, the main Western Wall Plaza prayer place is segregated by gender, as in accordance with traditional Orthodox Judaism. For those who do not espouse this way of thinking and living, this dividend poses a personal problem and the need for a space where men, women and those of other genders can pray, cantor and sing.

And this is where the topic of praying at the Western Wall becomes a sensitive and fragile issue. The arguments surrounding this new deal stem from many standpoints: historical, religious, spiritual, Jewish feminist, political, Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer (LGBTQ), and surprisingly even archaeological. Many are contesting to what they believe is accurate and appropriate behavior and prayer practice at the holiest place in the world. At the location of the Temple built by King Solomon, whose name means “peace,” not much peace stands right now.

—

In my high school, a very religious all-girls Jewish school, I loathed the daily hour-long morning prayers. I was furious at my school system for its narrow form of thought and instruction and I was saddened by God, for I felt so detached and unaccepted by him. At school, I was put in a box and I felt like a cookie-cutter black-and-white cookie. So, I daydreamed instead. I wanted freedom and the ability to control my own self-expression in terms of dress, adornment, opinion, and, perhaps deep down inside, prayer. I left that school with a bitter taste in my mouth for Judaism.

In my first semester of college, during the summer of 2011, I happened across the only class available: Cultural Anthropology, taught by Dr. Eric Minzenberg. (For reference: according to Texas A&M University, culture is “the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations through individual and group striving.”) My Weltanschauung changed upon learning two terms from Minzenberg: participant-observation and ethnocentrism. The former word can loosely be defined as an anthropological research method for studying culture, i.e., by simultaneously being an active participant and a passive observer. The latter word is “the belief in the inherent superiority of ones own ethnic group or culture.” After that class, I did what I vowed I would never do. I booked a flight to Israel to study my Jewish heritage one last time, but this time from an anthropological perspective in a Sephardic women’s seminary, Midreshet Eshel, in the Old City of Jerusalem.

During this time, I fought between two worlds: religious and secular. As an active participant, I prayed at the Western Wall with modest fashion and behavior, left a note, and took a photograph with a female IDF soldier. As a passive observer, I then sat in the Jewish Square with my college-level biology coloring book, studying science whilst occasionally surveying the behavior of people in my environment: tourists, clergy, children, workers, soldiers, family, friends and loved ones. And as I delved into the intricacies of cells and cellular processes as complex as cytokinesis and the citric acid cycle, the physiological essentials of human life, I no longer fought. I was developing my own special connection to God and an appreciation for his many beautiful yet complex creations, complex at physiological, psychological, and cultural levels. I was, in my own way and space, praying to God, thanking him for his presence, graciousness and miraculous wonders. Essentially, I was also connecting to my fellow Jewish people, (Yehudim, יהודים) whose etymological root, “hoda’ah,” (הודעה) means to give thanks.

Eventually, while at seminary, I opened up to a rabbi (whose name per his initial request shall remain anonymous) about my contrasting personal and religious struggle with Judaism. I explained how I saw Judaism — black and white, like the empty, uncolored pages in my workbook, and similar to the black suits and white blouses of chareidi Jewish men. In response, he told me, “Judaism is like a rainbow. It is a spectrum of colors. And everyone has a place in it.”

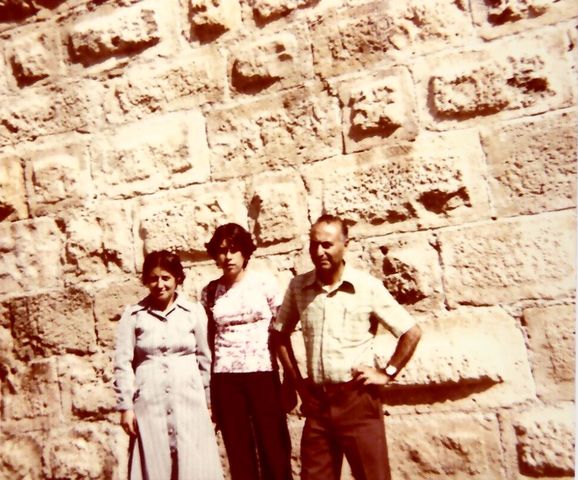

In a world of seven billion people, each individual sees the world from literally and figuratively different angles. Thus each individual will assert their own ethnocentric right. The lingering question surrounding the Western Wall controversy is not who is right. The Western Wall is an edifice of Jewish ancestry, a passing down of DNA for thousands of generations. From within a small space of the soul, every Jew wants their own personal, ingrained, non-superficial connection to Judaism. I found it through my spiritual journey at the Western Wall, like my grandparents, Helen and Eliyahu Soleymani, did before me, trekking from Iran to Israel in 1978 to pay a personal homage to our holy home. And that is the hope I have for my children, grandchildren, and all my fellow and beloved Jews, when they look back at their inherited (or adopted) history and cultivate their own niche within the many subcultures of Judaism.

Thus, the real question is: how will the Jewish people survive? Is it by holding on to tradition or forging something new? Or perhaps, is it individualistic, a sweet spot for everyone anywhere on the spectrum? Mark Twain said, “If the statistics are right, the Jews constitute but one quarter of one percent of the human race…a nebulous puff of star dust lost in the blaze of the Milky Way…(and) the Jew saw them all, survived them all…what is the secret of (their) immortality?” I wonder how the captain, the Rebbe, would answer.

*This article was written in blessed honor of my maternal grandparents and in dedication to the Lubavitcher Rebbe.