If a tree falls in the forest with no one to hear it, how can we prove it made a sound—and, years later, that it even fell at all? If six million people are murdered, with few images to bear witness, how can the reality of their loss endure?

As far as the Nazis were concerned, the truth can not be immortalized without evidence, and so, for much of the Holocaust they sought to erase it, systematically concealing their atrocities behind the walls of concentration camps, hidden from the outside world.

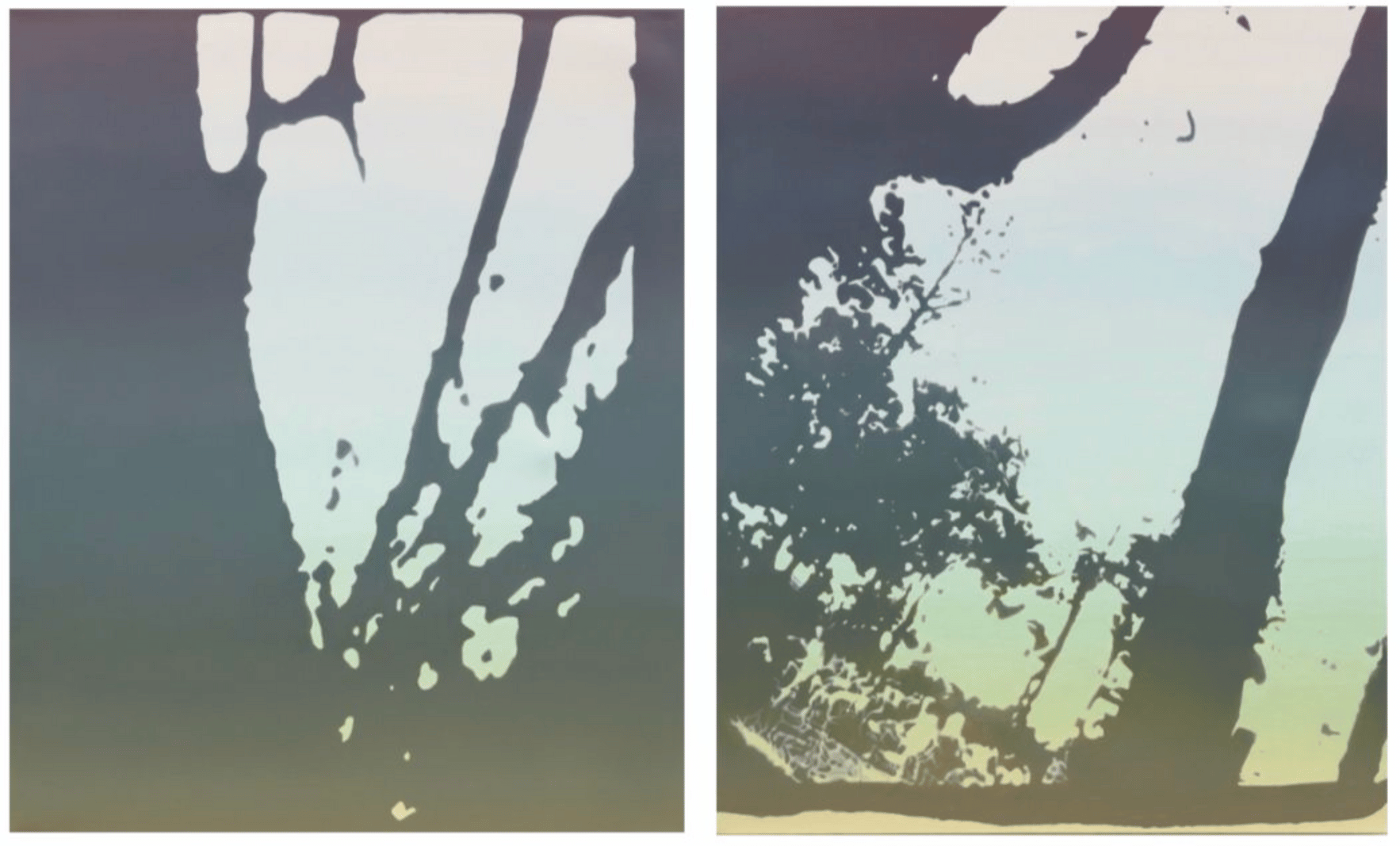

To resist this erasure, a few prisoners risked everything to capture the truth. Among them were members of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz—prisoners forced to aid in the camp’s operations—who, with a smuggled camera and the support of the Polish resistance, managed to take a handful of photographs in 1944. These images—blurred, hastily taken, and haunting—show bodies being burned and women as they are led to the gas chambers. They remain some of the only photographs of the Holocaust captured by its victims, revealing not only the horrific reality of the camps but also the profound ability of images to bear witness where words alone cannot.

These clandestine photographs served as both documentation and defiance. Taken under impossible conditions, they stand as acts of resistance and, in their stark honesty, powerful works of art. Resistance art is more than a record; it is a radical, enduring challenge to the censoring of history and a testament to the unyielding demands of memory. This significant art form not only preserves the tumultuous histories of many ethnic minorities but also facilitates the confrontation of collective trauma, initiating healing across generations.

These rare Sonderkommando images have been reimagined by Los Angeles artist Jacob Fenton, in his exhibition, Usufruct, which explores how art not only documents history but can transform trauma into a vehicle for reclamation and healing. “Through abstracting and obscuring these preexisting images, the paintings provoke a disturbance of cultural amnesia, forcing those who refute their Judaism or those who take refuge in dogmatic, conspiratorial beliefs to confront the memory of Auschwitz in the digital age,” writes Simon Brewer, Gallerist at Jeffrey Deitch and one of the curators of Fenton’s exhibition. By reworking these images, Fenton reframes them as invitations to engage with inherited pain, creating a counter-narrative that defies repression and calls for intergenerational empathy.

Fenton’s interpretations hold a place in a long history of trauma art—art that confronts, rewrites, and reclaims painful narratives. This is art with revolutionary power, a psychological “insurgency” against silence and oppression. Artists have been using their work to document suffering and galvanize resilience across cultures for centuries.

The Mexican muralists of the 1930s, such as Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, created bold public works that depicted Indigenous oppression, colonialism, and class struggle. Rivera’s murals, particularly those in the Secretaría de Educación Pública, inspired a collective identity among Mexican laborers, empowering them to see themselves as heroes and fueling labor strikes and protests in the 1920s and 1930s. These murals became a collective form of therapy—art as reclamation. Rivera’s works turned generational trauma into cultural pride and symbols of Mexican identity and strength.

Similarly, African American musicians like Billie Holiday used jazz and blues music to reclaim their cultural narrative in ways that would defy temporal and spatial bounds. Holiday’s Strange Fruit, a haunting portrayal of lynching, became an anthem of resistance against racial violence, resonating in anti-lynching campaigns and civil rights protests and embedding the resilience of Black communities within American cultural memory. Like Rivera’s murals, Holiday’s music used trauma as an enduring representation of strength to immortalize their true histories.

Beyond its psychological impact, emerging research suggests that art could play a role in influencing the biological markers of inherited trauma. Studies on epigenetics reveal that trauma can leave chemical marks on DNA—specifically in genes related to stress response—altering how descendants react to stress and creating inherited vulnerabilities (Yehuda et al., 2016). Notably, descendants of trauma survivors often have lower cortisol levels, associated with a heightened stress response, due to these inherited markers.

Yet, engaging with art has been shown to reduce stress-related biological markers in the body. A recent study found that art engagement can lower cortisol levels significantly in participants (Kaimal, Ray, & Muniz, 2016), suggesting that trauma-centered art could theoretically help “rewrite” some of these markers, allowing descendants to process and mitigate inherited stress responses. This groundbreaking notion implies that art inspired by trauma might do more than heal emotionally—it could alter trauma’s legacy on a physical level.

Art serves as an insurgency against inherited trauma, using the visual language of suffering to rewrite personal and collective histories. We are consistently reminded of its power to disrupt cycles of inherited pain, create new narratives, and even provide biological pathways for healing. Cultural art holds the promise of a future in which memory is not only preserved but becomes transformational—a testament not just to survival, but to the profound capacity of art to enhance what it means to remember.

Images provided by artist Jacob Fenton