An achievement in the school of physically oppressive cinema, Claude Laznmann’s The Last of the Unjust spans slightly more than three and a half hours and relies on two factors to compel its viewers to keep to their seats: the silent horror of empty concentration camps and locales in Central and Eastern Europe and the clever, magnetic, and provocative testimony — discourse — of Benjamin Murmelstein, arguably the eponymous “Last of the Unjust” (a play on the title of the famous novel by André Schwarz-Bart).

Revolving around the charismatic but controversial figure of Murmelstein, the last of the Der Älteste der Juden or “Elder of the Jews” of the Thereisenstadt concentration camp, the film is a series of interviews, filmed in 1975, with the only Elder (leader) not to have been killed during the Holocaust. Interspersed throughout Murmelstein’s narrative is Laznmann himself, exhuming the memories of places like Nisko (Poland), Vienna, and Thereisenstadt and revealing their terrifying permanence in contrast to the lives extinguished there.

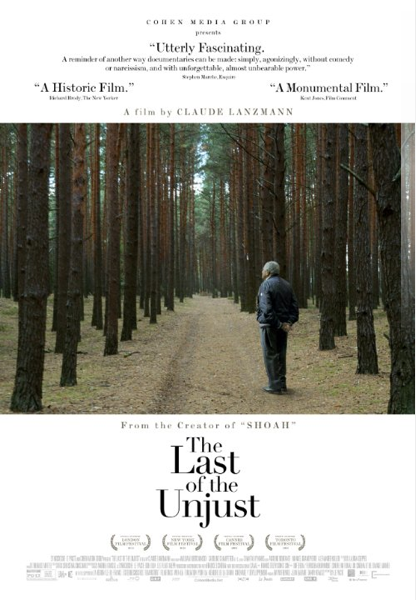

The three and a half hours of the film are, as mentioned earlier, difficult for the average moviegoer, and it seems as though Laznmann could have made the experience less demanding for the viewer if it had included any “breaks” of archival footage besides the famous Nazi propaganda film “The Führer Gives a City to the Jews.” But the longer one sits in the dark theater and watches the narrative alternate from Murmelstein’s charismatic story (perhaps even his “self-defense”) to Lanzmann’s readings of Murmelstein’s book, Terezin: Il ghetto-modello di Eichmann (Theresienstadt: Eichmann’s Model Ghetto) and the director’s slow, reflective walking tour, the more one realizes it is calculated cinematic technique, to foist on the viewer a feeling of an unthinkably heavy weight and to compel him to abandon the self-imposed responsibility of passing judgment.

Murmelstein’s intelligent, articulate, and rather detached demeanor while recounting the Holocaust and his role in it — whatever one decides it was — might serve to calm or to infuriate the viewer, to vindicate or vilify Murmelstein’s account. Many might not like the focal point of the film or may even feel angry with its principal character, but it is important to differentiate the characters in a film from the actual film itself, and to remember that perhaps it is an achievement of truly great cinema when one reacts so strongly to anything therein.

A fascinating film, a film worth seeing, a deeply troubling film, and, above all, a “good” film (whatever its definition is) are not mutually exclusive definitions; these are categories into which this film might fall into, but is not completely characterized by. The film is unsettling and provocative — and for those who do not wish to take the time to consider context, history, or the fallibility of the human conscience, it will be easy to write the film off as an advocacy or as a “defense” of a collaborator. But by giving Murmelstein a chance to speak and tell his piece of history, by including the small but deeply informative reactions of the filmmaker himself, and, above all, presenting the narrative to the viewer to judge, what is imparted to the viewer is not a defense with a solid judgment. In fact, it is not even an invitation to make a judgment. Rather, it is a question and a memory that stay with the viewer long after the film is finished. Mr. Murmelstein himself transformed the idea into a single troubling statement and put it best: “A martyr is not a saint.”