Clipse, arguably the greatest coke rap duo of all time, has a Jewish problem. In their successful single “Wamp Wamp,” the pair uses an unfortunate metaphor to describe a step in the process of cooking cocaine: after they remove the coke-filled pan from the oven, “It cools to a tight wad — the Pyrex is Jewish.” The “cheap Jew” stereotype was also used by Jay-Z in “This Can’t Be Life,” where he raps “Flow tight, like I was born Jewish.” (Jay-Z uses the adjective ‘tight’ to refer both to his musical talents and to the stereotype that Jews are tight with their money.)

More broadly, however, Jews are caricaturized as wealthy professionals. Rick Ross, showing off his wealth on Drake’s “Lord Knows,” brags: “Villa on the water with the wonderful views — only fat n**** in the sauna with Jews.” And Mos Def, a pioneering conscious rapper, maintains in “The Rape Over” that “[a] tall Israeli is running this rap s**t” (referring to Lyor Cohen, the current CEO of 300 Entertainment and previously top dog of Def Jam and Warner Music).

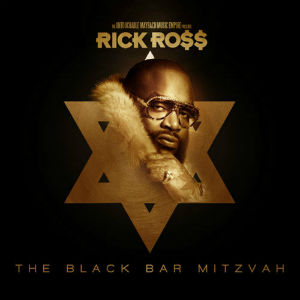

In a similar vein, Jewish lawyers have become a status symbol for rappers, likened to gold chains and Lamborghinis by those who wish to declare that they own the best that money can buy. Rappers who have shouted out their Jewish lawyers include Kanye West (“Diamonds blue, his business manager’s Jewish — and if I get sued, my lawyers Jews”), Jay-Z, Drake (“I got a Jewish lawyer as my main defender — a real Menchkeit, as they say, he’s a legal bender), Killer Mike, Chief Keef (“Bodies drop, we beat the case — my Jew lawyer defeat the case), A$AP Ferg, Vince Staples, and Action Bronson, as well as many others who are less well-known. Bronson, who has Jewish ancestry, seems especially enthusiastic about his Semitic litigator, referencing him in at least four of his songs and imploring his listeners to “employ a lawyer who’s been Bar Mitzvahed — never trust the Goyim” in his track “Morey Boogie Boards.”

In the cast of characters that rappers draw on, Jews are not the only ethnic group typecast in an extremely narrow role. East Asian women, for example, rarely transcend the role of sex objects.

But rap does not invent the stereotypes that it exploits. Stereotypes about cheap Jews or oversexualized but submissive Asian women are much, much older than rap music. However, the unique rules governing hip hop allow these stereotypes to be spoken more explicitly. Relatively permissive standards for lyrical content allow rappers to say explicitly things that would go unsaid in most American cultural contexts. Furthermore, rap lyrics often contain characters who are portrayed in very simple terms, making it difficult for a character to develop complexity beyond the simplified box of a group stereotype. (The factors that contribute to this leniency in political correctness within the rap genre are many, and virtually unverifiable — thus I will not dwell on them.)

However, this is definitely not a universal rule. Kendrick Lamar may be one of the greatest authors of our generation, and many other rap artists also develop highly nuanced characters in their lyrics. Nevertheless, flat, prop-like characters are fairly common in the genre.

Rappers did not invent the “cheap Jew” and “rich Jew” stereotypes, and they aren’t fully responsible for perpetuating them. These stereotypes still exist in broader American culture, and the unique rules governing rap simply make them more explicit. Rappers are no more responsible than anyone else for the perpetuation of the stereotypes that they exploit. Despite the clarity with which hip hop can express anti-Jewish stereotypes, its messages should be viewed merely as a symptom of a subconscious undercurrent of similar beliefs in broader society.