Should ordinary citizens in a society be held accountable for the negative actions of their leaders?

This type of question is consistently discussed by sociologists, moral philosophers and military strategists alike. One can find thousands of pages, written over the course of centuries, on the morality and legality of collective punishment.

Perhaps the greatest benefit of being a part of the Jewish tradition is that we have roughly a 3,000 year head start when it comes to thinking about many questions, including the question of collective punishment.

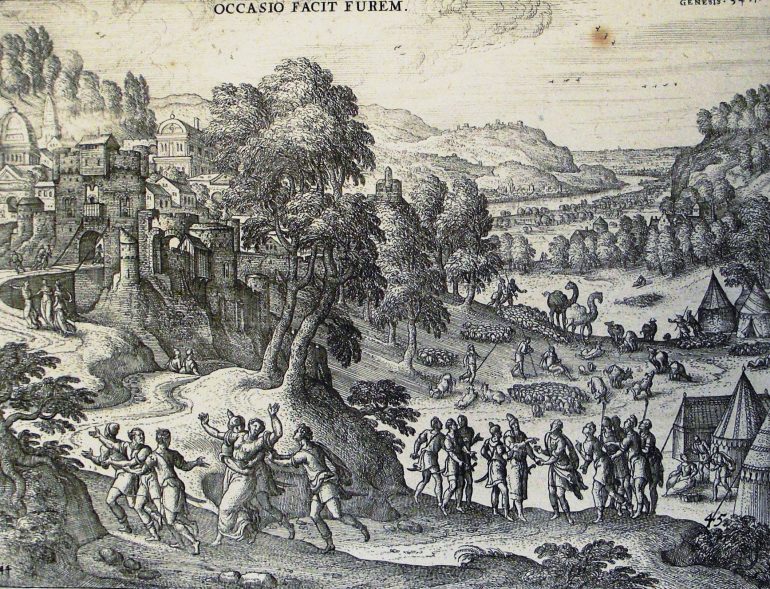

In our Parsha, Jacob’s daughter Dinah is taken captive and violated by a prince named Shechem. Subsequently, Shechem’s father, Hamor, attempts to smooth things over by proposing a deal with Jacob’s family. He would pay them off in return for securing Dinah for his son. Now overt sexism aside, Jacob and his sons agree to the deal, but only if the entire city would be willing to circumcise themselves — which they did. Then, while the men of the city were healing from their circumcisions, two of Jacob’s sons, Shimon and Levi, massacred the populace. Jacob’s reaction to this act seems to be negative, but he may have been more concerned about the political ramifications than the ethical ones.

Like so many other stories in the Torah, the text of this narrative is extremely short and elusive. There is much background missing, leaving the reader begging for more information and answers. This is where Jewish traditions comes to the rescue.

Over the past 2,500 years, this story has been dissected, defended and decried in every way imaginable. Flipping through the various books in the Beit Midrash we can read every argument possible on both sides of the collective punishment debate. And, the best part is that all of this knowledge is available, even if we do not share any of their same religious presuppositions.

We often think of the ancient Rabbis of the Midrash as infallible men who had various traditions dating back to Sinai or the they had some sort of divine inspiration and were therefore attuned to information beyond our reach.

Nope. These Rabbis were ordinary people like us (well, probably slightly more nerdy), who used their own life experience and moral judgment to make claims about and to interpret texts. Whenever we sit around reading and discussing these stories we are following directly in the path and tradition of our ancestors.

Therefore, I will not give you an answer to the question I have posed. Instead, I encourage you to go to the Beit Midrash and explore the diverse writings on this subject. This is, after all, just a “Taste of Torah” — if you want the full meal, you’ll have to work for it.