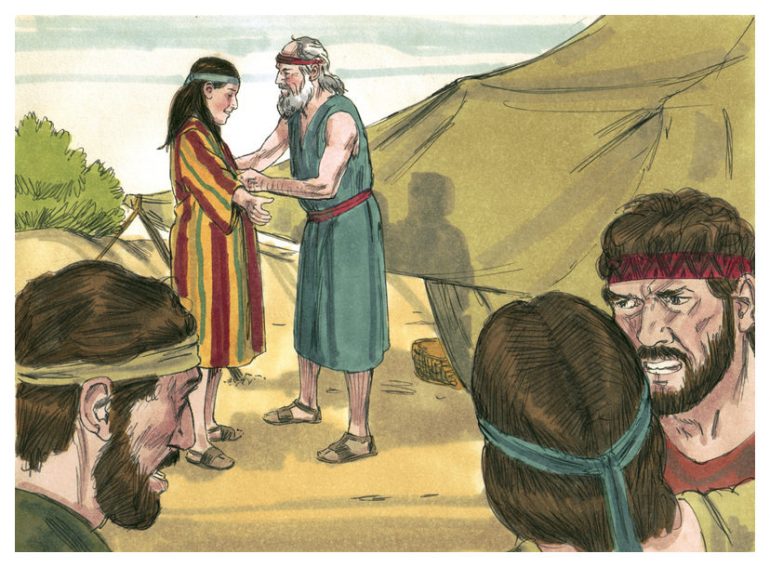

Clothing is a leitmotif in the Joseph narrative. His father gifts him the coat of many colors; his brothers rip it off his back and dip it in blood; Potiphar’s wife grabs his shirt as he flees from her advances; he is given new clothes when he is released from prison to interpret Pharaoh’s dream; he is bedecked in royal garb as he is elevated to second to the throne of Egypt; and he gives clothes to his brother Benjamin when they are reunited.

What is it with Joseph and his clothes? Why couldn’t he keep his shirt on his back?

The “coat of many colors” gifted by Jacob to his son Joseph (Genesis 37:3) has a strange origin. According to the Midrash this coat was the very garment made by God and given to Adam after he ate the fruit! It was passed from generation to generation through Nimrod and, eventually, to Esau—from one first born to the next. It was this coat that Jacob took as part of the bechorah (privilege of the first born he bought from Esau) and wore when he deceived his father, Isaac, masquerading as his brother (“When Isaac caught the smell of his clothes, he blessed him and said, “The smell of my son is like the smell of a field (read: Garden of Eden) that the Lord has blessed.” (Genesis 27:27)) And it was this very coat that Jacob gifted to Joseph at the beginning of Parashat Vayeshev.

The coat, then, was not (just) a symbol of fatherly love or favoritism and the brothers’ resentment was more than petty fraternal jealousy and sibling rivalry. The coat was the symbol of leadership. With its transfer, Jacob was anointing Joseph as the head over his brothers and the heir to the leadership of Jewish destiny.

But there was one problem… the coat was (metaphorically) too big for his shoulders. Joseph, a na’ar (immature lad, Gen. 37:2) of seventeen had not yet evolved emotionally, intellectually, and in character and ability, for this role. In fact, the whole Joseph narrative, with all its ups and downs (thrown into a pit and sold into slavery, rising in Potiphar’s house only to be jailed, and eventually being appointed second to Pharaoh) is the story of the not-so-straight path of the evolution of Joseph into Yoseph ha-Tzaddik (Joseph the righteous), the mature and dynamic leader on the world stage. At various points in his biography he “tried on” different garments for size. They were his costumes, his masks– his persona. Carl Jung described the persona as the social face a person presented to the world—”a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and on the other to conceal the true nature of the individual.” And each time it “didn’t fit,” each time he bit off more than he could chew and found himself in situations that were beyond his ken, the clothes were literally ripped off his back.

Time and again the clothes don’t quite fit, until finally Pharaoh dresses him like a king (Gen. 41:42) and this time it is a perfect fit! Joseph had evolved and was worthy of the mantle of a leader. The greatness of Joseph is not that he was born perfect, but, rather, that he withstood his ups and downs and, most importantly, learned from them. He dreamed of the clothes he wanted for himself and, with grit and determination, succeeded in wearing them. He learned—the hard way—that it is not the clothes that make the man, it is the man who makes the clothes! And that is what earned him the Rabbis’ appellation of tzaddik (righteous one).

The university years, for many, are filled with ups and downs (hopefully, for most, not of the Joseph kind). We try on different garments and experiment with different masks—academically, socially, politically, philosophically, religiously—trying to figure out who we are, who we want to be, and where we want to go. While this can be an exciting, dynamic time, it can also be one of uncertainty, anxiety, and (forgive me) existential angst.

Please allow one piece of advice: Like Joseph, don’t alter your “clothes” to fit who you are right now. Brace yourself for the ride, thrive in your successes and bear your failures, and work hard to fit into that “coat of many colors” that is your destiny as an individual, a member of your family and community, and as part of the Jewish people.