Trudging up or down Bruin Walk, one sees students advertising events or organizations, hawking wares, or simply skirting gaggles of visitors to UCLA. However, those passersby on Oct. 15 and 17 witnessed a campus-wide march to protest California’s Proposition 206, which in part prohibits affirmative action, in light of the upcoming United States Supreme Court case Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, Michigan’s law of similar language.

Thirty-five years ago, the Supreme Court ruling in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke ended a furor across the United States, especially among college-age students. The Supreme Court upheld the legality of affirmative action while prohibiting race quotas, regardless of whether such quotas were to ensure diversity or supremacy. In 1996, Proposition 206 was passed in California, banning the consideration of race in public schools’ admission decisions, and today, racially influenced personal circumstances are one component in the University of California’s “holistic” admissions system.

Most recently, the Michigan Civil Rights Initiative (Proposal 2) was passed in Michigan in 2006. The proposal amended the state’s constitution to “prohibit the University of Michigan and other state universities, the state, and all other state entities from discriminating or granting preferential treatment based on race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.” In effect, it prohibits affirmative action, since the practice involves the favorable consideration of candidates who identify as ethnic minorities over the consideration of those who do not.

The proposal’s legality was challenged in federal court and ruled constitutional in 2008. However, the U.S. Court of Appeals (Sixth Circuit) overturned it in 2011 under the ruling that it “place[s] special burdens on minority interests.” The state’s attorney general, Bill Schuette, appealed the Supreme Court’s verdict later in the year but the decision was upheld in 2012. Schuette then appealed the verdict to the U.S. Supreme Court and it is currently pending. The oral argument began Oct. 15 and the Supreme Court’s decision is to be announced by the end of the current term — May, June or possibly July.

The verdict would not seem to affect admissions to the UC, since the aforementioned Prop 209 is already in effect, and race is simply a factor in the overall decision. California also guarantees the top four percent of every accredited high school in the state admission to at least one UC campus, as a way of ensuring that at least some students from minority neighborhoods are matriculated. However, organizations such as the Los Angeles chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People are calling for the proposition’s repeal. In 2011, a UC Berkely-based coalition of student groups from UC Berkeley, UCLA and other schools, along with the UC Berkeley chancellor, publicly advocated for the same. An amendment to the proposition is currently in the judicial works and could be on the voting ballot in a few years.

The Supreme Court’s verdict on Schuette will undoubtedly have significant repercussions on affirmative action and racial discrimination laws, no matter how it rules. If Proposal 2 and Proposition 206 are overturned, the status of those considered to be white (or not members of ethnic minorities) will likely be affected by Schuette’s outcome. As most Jews today are considered to be racially white, the future of Jewish admissions to UCLA might be affected as well.

Jews of European, Middle Eastern and/or North African descent have not always been considered racially white. In How Jews Became White Folks and What That Says About Race in America, Karen Brodkin of UCLA’s Anthropology department explains that Jews were originally considered to be a separate, inferior race outside of other races. “White” was a broad category that was subdivided by national origin as well as skin color. However, by the 1940 U.S. Census, one’s country of origin was no longer taken into account for the racial definition of whiteness, as pertaining to Europeans and those of European descent. Increased prosperity and upward social mobility due to GI Bill benefits (for whites) also allowed more Jews to join the United States’ growing middle class.

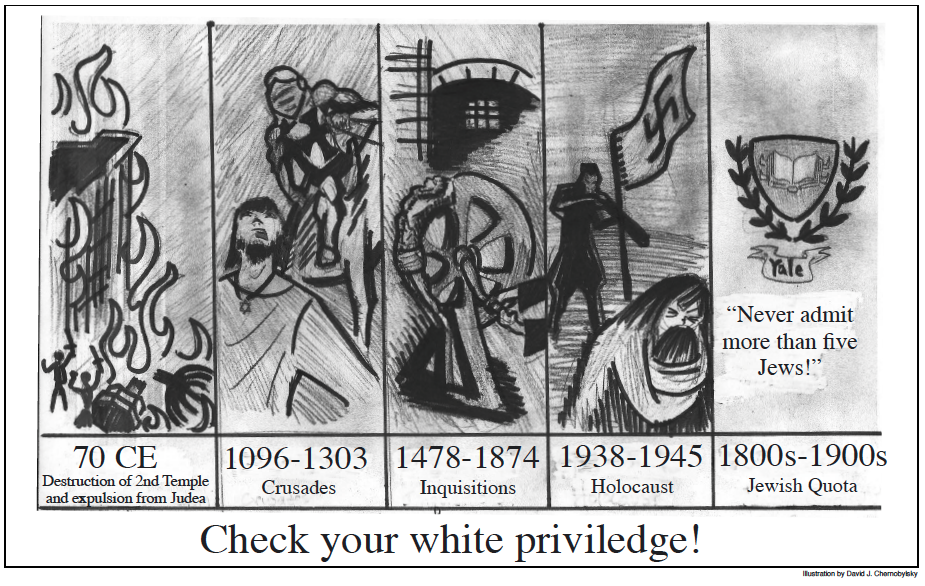

Until late in the 20th century, “Jewish quotas,” or restrictions on the number of Jews to be admitted to institutions of higher learning, were in place in many prominent universities such as the Ivy Leagues and other elite schools like the University of Chicago. Jews were viewed as a distinctive group alongside African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and, for a number of years, women. As Alan Dershowitz of Harvard University’s School of Law describes in his 1991 book Chutzpah: “In 1926, Clarence Mendell, the new dean of Yale College, was told by Harvard’s admissions chairman Pennypacker that Harvard was ‘going to reduce their 25% Hebrew total to 15% or less by simply rejecting without detailed explanation.’” In 1935, Milton Charles Winternitz, the dean of Yale Medical School gave the admissions committee precise instructions to “[n]ever admit more than five Jews, take only two Italian Catholics, and no blacks at all.” Dershowitz alleges that quotas were in place, albeit less openly, until about 1971, when he and other Harvard faculty members confronted the newly-promoted head of the law school about faculty appointments based on religion.

As successfully as Jews have integrated into much of middle-class America, David Myers of UCLA’s History Department and Center for Jewish Studies describes a two-sided approach in that very integration. “…Jews are considered by many in American society to be white. At the same time,” Myers says, “Jews continue to harbor the memory of of their forebears’ persecution and travails, which inculcates in them a sensitivity to the plight of others.” This cultural memory, he explains, contributes toward the overall Jewish trend of endorsing more liberal governments and stronger protection of minority rights. It may also be an argument against Jewish inclusion among those who have historically enjoyed white privilege, or societal privileges at the expense of others.

“Race,” as Brodkin explained in an interview with Ha’Am, “is a social construct.” While programs such as affirmative action may help those with a history of underprivilege, it does not take into account those do not fit neatly into one category or another. However one views oneself — as African-American, Caucasian or Oompa-Loompa — for many Americans, race continues to be an integral part of self-identity. It now remains to be seen what the Supreme Court will have to say on the subject.