How can it be that there are so few religious Russian Jews left, when the vast majority of 18th century Jews lived in the Russian Empire? In fact, it is estimated that the Russian Empire had a population of 5.25 million Jews in 1897. How does a group that large lose its orthodoxy and disappear into secularism? With the exception of a rare few, Russian Jews don’t tend to be religious. This might have something to do with the fact that Judaism has been a clandestine religion in the underground parts of Russia for the last few centuries.

Antisemitism in the Russo-Slavic region of the world stems from before Stalin’s time. In the late 18th century, the Russian Empire (the precursor to the Soviet Union, and eventually Russia) obtained a massive Jewish population, and was faced with “The Jewish Question”: What to do with the Jews? Catherine the Great, Empress of the Russian Empire from 1762-1796, answered this question by creating the Pale of Settlement, which created specific zones in which Jews were permitted to live. Consequently, Jews were prohibited from living in the bigger, more urban cities, such as Moscow or St. Petersburg — although with a certain license, they could practice business within those cities.

During this time, new ideas of secularism and of the Enlightenment started thriving, changing the structure of Europe, in turn affecting Jews dramatically. Liberalism began in Germany, birthing the Jewish reformation, which aimed to integrate Judaism into mainstream society. Shabbat was moved from Saturday to Sunday, many Jews no longer kept kosher, organs could now be played at shul, etc. Some Jews went so far as to abandon their Jewish identity altogether. Karl Marx was one of these Jews — at the age of four, Marx was converted to Protestantism, as his family believed that Protestantism would be the ticket to a life in high society. Slowly but surely, traditional orthodox Judaism was being lost.

This vision eventually spread eastward into Russian territories, diluting traditional Judaism. In the 1820s, Poland and the Russian Empire were influenced by Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment movement. It was an attempt to make Orthodox Russian Jewry more modern — a better fit for contemporary society.

Intellectual movements aside, Russian Judaism was also influenced incredibly by the Russian rulers. The alternating czars of the period were drastically different from one another — some being beneficial to the Jewish people, while others were detrimental to the existence of Jews in Russia. Although Czar Alexander I was good to the Jews; Czar Nicholas I was anything but, plotting to split Jews into three groups: one-third to be expelled from the empire, one-third to be converted to Christianity, and the rest were to simply be discriminated against.

Nicholas reformed the law prohibiting Jews from serving the army so as to draft them. Jewish boys as young as eight years old were taken from their homes and enrolled in a preparatory army program. Then, beginning at age 18, they were required to serve a 25 year conscription. The purpose of this system was to ensure that Jewish men would be raised in non-Jewish environments for as long as possible, so as to disconnect from their Jewish identity. Czar Nicholas I also aligned himself with the Jewish reformers because he believed it would erode the traditional Jewish education and help assimilate Russian Jews into the contemporary culture.

While Alexander II was more benevolent towards the Jews, his successors, Alexander III, and later following, Nicholas II, were both openly anti-Semitic. Jews were scapegoated for the assassination of Czar Alexander II, and his successors wanted revenge. At this point, Judaism was practiced underground because the Czar encouraged pogroms — organized massacres or mob lynchings of Jews.

The word “pogrom” comes from the Russian word gromit, which means to destroy via violence. These pogroms were occurring all over the empire, particularly in major Slavic Jewish cities such as Kishinev, Odessa, Kiev, Warsaw, and Bialystok. The time from 1881 to 1884 was the bloody peak of this violence, amounting to about 200 pogroms.

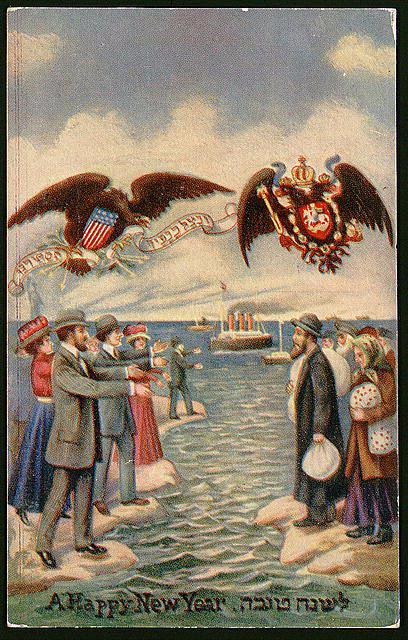

Russian Jews feared for their lives, and this increasing violence resulted in major migrations. During the years 1881 to 1895, 2.5 million Jews migrated out the Russian Empire. Not too long after, the second great migration of Jews occurred between the years of 1903 1920.

The pogroms and anti-semitism eroded Jewish life in the Russian Empire. By the start of World War II, Jews had to be evacuated from the border, away from Hitler’s incoming army. At this time, Jews were forced to pick one of three routes: Zionism, socialism, or death. Zionism gained popularity because it was perceived as a secular form of security for Russian Jews; to many it emphasized that Russian Jewry didn’t need religion necessarily — just a country to be safe in.

Other Russian Jews chose socialism. This, too, was secular in nature, and gained popularity amongst Jews and non-Jews alike. The youth especially believed that communism was a their ticket out of discrimination, because the ideology advocated that workers are equals. In addition, socialism gave a glimmer of economic hope, for the majority of Jews in the Russian Empire were poor.

During the Russian Revolution, Jews fought on behalf of both the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks (or the Reds and the Whites, respectively). When the Bolsheviks were victorious, and Lenin took power, any type of religion was deemed illegal. The communists established a secular Jewish section of the communist party called yevsektsiya, hoping to effectively target religious Jews by using secular Jews.

Moreover, new laws were implemented that made keeping Judaism difficult — such as making a 6-day school week, forcing students to attend class on Shabbat. Students were encouraged to snitch on their parents for doing anything even remotely religious. Parents would be arrested for practicing Judaism, and many children would be put into orphanages — causing them to lose touch with their Judaism. Many religious leaders left the Soviet Union, so the remaining Jewish people had few to look up to.

After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin succeeded as the leader of the Soviet Union. His extremely paranoid and anti-religious persecutions were an intensification of Lenin’s, utilizing secularized Judaism to persecute religious Judaism to a greater extent. For instance, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the leader of underground Judaism, was tortured by secular Jews. Moreover, Stalin encouraged a Yiddish theater and newspaper, but there was a catch: they had to be secular and cultural. Moreover, Stalin actually established the first “Jewish State” — the Jewish Autonomous Oblast — located on the far east part of Russia, close to Japan.

During WWII, Stalin made a deal with Hitler, resulting in the Soviet Union’s conquering of Poland, Lithuania and several other Baltic states, which were heavily populated Jewish regions at the time. For many Jews, coming under Soviet rule appeared to be the lesser of the two evils. Although they were forced into hiding their Judaism, at least they were spared their lives; during this time, the Jewish population doubled in the Soviet Union. Many Jews even fought for the Soviet army against the Nazis.

After the war, Stalin, in an effort to maintain equality and egalitarianism amongst all Soviets, did not acknowledge the Jewish loss in the Holocaust; claiming that the Soviet citizens that were the targets of the Nazis, and made no mention of the devastating loss of Jewish life. In 1952, Stalin feared doctors were “out to get him,” resulting in the targeting of Jewish Russian doctors. In Moscow, a few Russian Jewish doctors were accused of conspiring to assassinate him. A year later, on March 5, 1953, Stalin died of a brain hemorrhage — ironically, if he had let his doctors take care of him, perhaps they would have been able to prevent the stroke that instigated his death. Stalin died before he could carry out the final solution in his doctor paranoia: the eviction of Jews to autonomous areas of Siberia.

Five years before Stalin’s death, the State of Israel was established. The Soviet Union was second to recognize Israel as a state, behind the United States of America. Despite the Soviet Union’s anti-Semitic tendencies, it wanted this Jewish state as an ally in the Middle East, with the hope that Israel would help spread communism. However, because Israel was democratic, she aligned herself with the Americans and the French. The Soviet Union then changed its strategy and quickly became anti-Israel, aligning itself with other Arab countries. It was the Soviet Union that provided military aid to Israel’s enemies and helped instigate the Six Day War. Today, Russia still poses difficulties for Israel, and for its own Jewish population.

Despite the hardships that Russian Jews endured, many did the best they could to keep Judaism alive. The codename was for head rabbis was “dedushka” (Russian for “grandfather”) and they communicated with one another in a clandestine manner. Jews exiled to Siberia wrote entire prayer books from memory in hopes of keeping their magnificent religion alive. The Russian bloc is a place with a dark past for our people. Because secularism was really the only way to get by, Judaism became a cultural or national identity, rather than a religious one. More than three generations of Russian Jews were raised without religious Judaism — so can we really blame the modern loss of religious Russian Jews? No, but we can continue to learn, and to take advantage of the Jewish opportunities we have here — and if not for ourselves, then for our ancestors who endured so much to keep Judaism alive.