From Fall 2016 Print Edition, “Transitions”

“God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him.”

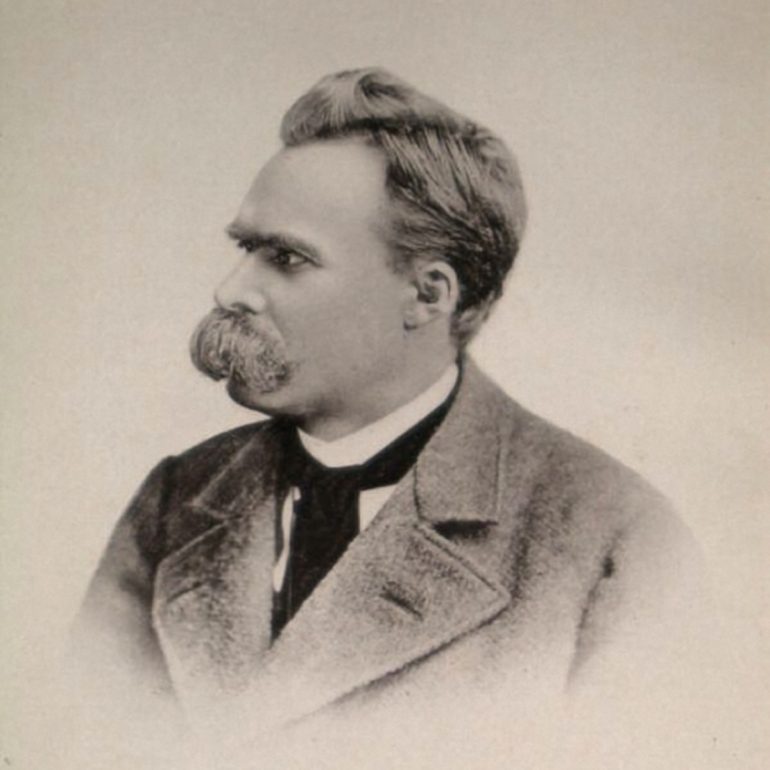

Friedrich Nietzsche is most memorialized in popular philosophy by this catchy, contentious extract from The Gay Science, published in 1882. For all of the ire this quote has drawn, the controversy it has generated emanates more from the brazen heresy of Nietzsche’s diction than from the actual meaning of the words.

Nietzsche did not argue that God was once a living, animate entity that humans physically or spiritually murdered. Rather, he observed that the progress and knowledge of the Enlightenment led people to reject God and thereby no longer depend on God or the concomitant religion that God symbolizes for absolute moral guidance. God was dead not as an entity but as a construct — the purpose of God as a source of morality was no more. Nietzsche feared that a society guided by moral relativism would follow, in which no value could be said to be objectively just, right or superior to another. Nietzsche spent his life attempting to uncover a deeper corpus of objective morality beyond that inspired by God, leading to his equally notorious perspective on “the will to power.”

Still, many religious detractors misunderstand Nietzsche’s quote as a blasphemous denial of God and religion; they view it as a pointed attack on their theological credo, even though Nietzsche values the concept of God as source of social structure and societal order. Of course, they are right in that Nietzsche certainly does not view God as an omnipotent, benevolent Creator of the universe or through any other religious lens.

But Nietzsche does not merit any more defense. More than 130 years later, both Nietzsche and his religious detractors are wrong about the death of God. God is neither dead, as Nietzsche argues, nor alive, as his religious detractors counter; rather, God is undead.

Despite the progress of the Enlightenment and of 20th century science, medicine, technology and philosophy, the contemporary world is fueled by and dependent on God to function. Indeed, despite a repository of knowledge more voluminous and more accessible than any in history, many lean more and more on dogmatic religious principles. Despite deeper understandings of the best ways to structure governments, countries around the world continue to fall to authoritarian religious dictatorship.

God is very much not dead, in the sense that religious practices and tenets still pervade laws and societies throughout the world. God is very much not alive, however, in the sense that so much progress has been made in advancing scientific understanding, and some reject God as a direct result of this new knowledge, as they did in Nietzsche’s day.

The only conclusion, then, is that God is undead. Much like a zombie, ordinary circumstances (the advancement of reason and science) dictate that God is dead. With a zombie, those ordinary circumstances are natural laws. However, the extreme devotion to God and fundamentalist religion persists unabated in much of the world — defying logic, much like a zombie’s mere existence defies logic, and indicating that God is alive.

In a report he researched and published on religious fundamentalism, Professor Michael Emerson of Rice University concluded that the world has experienced an uninterrupted upsurge of religious, fanatical extremism since 1970. He cites ISIS, Boko Haram, Hamas and Al-Qaeda, among others, as examples of a movement toward fundamentalism in much of the world — a phenomenon visible to anyone who follows current events.

However, Emerson’s report neglects that this rise in religious fundamentalism happens even as scientific progress continues to outdo itself. Every day, advances are made that bring the world to a better, more progressive place, whether those advances involve developing groundbreaking new cancer treatments, novel agricultural methods to sustainably and productively grow crops or anything in between. Since extremism has continually worsened over the last 40 years, the gap between those who have adopted science and technology and those who have not has widened.

Despite knowledge of how to do better in all facets of life by espousing secular or moderate religious practices, the world is evolving dangerously into a place controlled by religious fundamentalism, not by reason. The undead nature of God is by definition problematic to human progress — it plays directly into the primary atheist criticism of religion: that its unabashed, unqualified following stunts societal progress.

Of course, theists raise a valid point that religion does have value and reason does have its limits. It can be quite presumptuous and arrogant to assume that man can explain every puzzle of nature with reason, alone. Theists highlight that using reason alone and ignoring speculative or faith-based reasoning is like using a hammer to secure a screw, to unscrew a light bulb or to brush your teeth. It is the right tool in some circumstances, but not in all.

Still, an undead God does not have to render these pro-theist arguments invalid. Nietzsche’s point in declaring the death of God was not that the world should reject religion but that it had and that it would inevitably succumb to nihilism, a clear inhibitor to human progress. At the moment, the existence of an undead God has the same effect of inhibiting progress.

Using speculative reasoning — defined as any reasoning process not predicated on or rooted in reason — might be necessary at times. It is impossible to understand certain phenomena in the universe without it. But its adoption in circumstances that warrant reason is dangerous to society, and the society that fails to use reason in the right circumstances — a society with an undead God — must work to continue progressing.