Not just a public-health concern! A holiday hypocrisy!

Coming from a proud Persian family, my exposure and experience with hookah was an integral component of family life. As a young girl, I vividly recall parties where my family, particularly the men and elders, would gather outdoors under my aunt’s orange tree and share wafts of smoke from the hose of the ornately decorated waterpipe. The aroma was enticing and exotic with different flavors every time, from classic mint to modern watermelon. Hookah, a vaporized form of tobacco passed through a water basin before inhalation, originated from Persia during the Safavid Dynasty in the seventh century. Frankly, hookah hails from my homeland.

Today, smoking hookah is a popular activity in mainstream cultures, with religious institutions also following suit, albeit with their own twist. UCLA’s Westwood area has two hotspots for Middle Eastern hookah lounges. Jewish religious organizations have even incorporated this popularity into their religious events. Most recently, countless Jewish organizations across the country, including Nessah Young Professionals (NYP) and UCLA’s Jewish Awareness Movement (JAM), hosted “Hookah in the Sukkah” parties during the Jewish holiday of Sukkoth.

Mati Geula Cohen, Chairmen of NYP, elaborated that the intention and goals of their “Hookah in the Sukkah” party was “to engage the Jewish young professional community through immersion in an authentic Middle Eastern ambiance centered around the sukkah so to reinforce the connection to the holiday, Jewish identity, and Jewish Semitic indigeneity.”

While I did not attend NYP’s event, I did attend JAM’s “Hookah in the Sukkah” event. Contrary to a statement provided by Mrs. Bracha Zaret, director of JAM, that “hookah in the sukkah was a welcome party whose focus was the sukkah not the hookah,” I can testify that there was absolutely no sukkah for the hookah in the party vicinity.

Cohen is definitely spot on with the reasoning why a “Hookah in the Sukkah” party is such a hit: “who doesn’t like a Middle Eastern themed event with authentic foods, mint tea, music, and hookah water pipes?” However, while such parties invite appeasing allure with its ambiance, food and social networking oppurtunity, a hookah-promoted party raises not just public health concerns but also a spiritual concern.

Knowledge of the health risks associated with tobacco-use have only surfaced as early as the 1930’s, thousands of years since the innovation of hookah. Despite myths that the deadly dangers of tobacco-use is only attributed to cigarette smoking, according to the American Lung Association (ALA), hookah smoking carries many of the same health risks as cigarette smoking. Just like cigarette smokers, hookah smokers are at risk of oral cancer, lung cancer, stomach cancer, reduced lung function and decreased fertility. According to UCLA professor and international expert on cancer and epidemiology, Dr. Zuo-Feng Zhang, a smoker has ten times the chance of getting lung cancer and has on average ten years less of life.

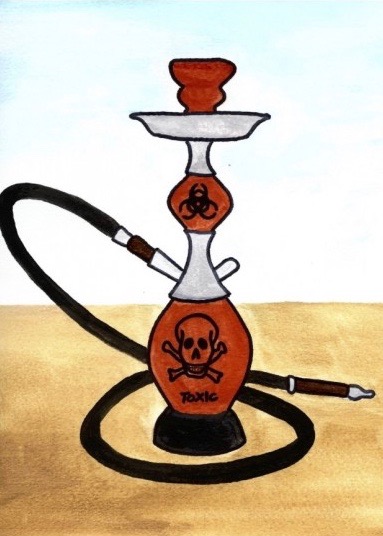

Zhang notes that the health risks associated with smoking stem from many ingredients and not just tobacco. Smoking exposes the smoker and those in the vicinity to four solid chemicals and 81 carcinogens (cancer-causing chemicals). Like cigarettes, hookah delivers nicotine, a highly addictive drug, to the body. One drop of nicotine, equivalent to forty cigarettes, leads to immediate death. According to the University of Maryland Health Center, compared to a single cigarette, “hookah smoke contains higher levels of arsenic, lead, and nickel, 36 times more tar, and 15 times more carbon monoxide than cigarettes.” Contrary to popular myth of hookah being a healthy alternative, Dr. Roger Detels, professor of public health and Chair of the UCLA Department of Epidemology, notes that “what the hookah does is send the smoke through water [but] that does not remove the impurties by any means” and “will not elimate the risk.” Because of the way hookah smoke is used, smokers may actually absorb more toxins than smoking cigarettes. An average hour-long hookah session involves 200 puffs and 90,000 milliliters (ml) of smoke, while smoking a cigarette involves 20 puffs and approximately 550 ml of smoke (ALA).

The horrors of “Hookah in the Sukkah” parties are not only related to health but also to holiday hypocrisy. Sukkot, the biblical pilgrim festival of booths, commemorates not only the end of harvest time and agricultural year in Israel, but also the Exodus from Egypt and dependence on G-d’s will. During this forty-year period, the Jews wandered in the Sinai Desert, dwelling in temporary abodes. More significantly, the Jews were protected from the dangers of the desert, such as heat, scorpions and predators, by G-d’s “clouds of glory”. Today, Jews celebrate this physical protection, G-d’s kindness and our trust in Him, by dwelling in huts for seven days. In essence, the Sukkot holiday is an appreciation for and emulation of God protecting the Jews’ bodies from harm. Smoking unhealthy hookah within the sukkah goes in direct opposition of the Sukkot holiday and the health message it symbolizes.

Even further, laws within the Torah assert the responsibility to safeguard the health of oneself and others. In Deuteronomy, one positive commandment states, “when you build a new house, you shall make a guardrail for your roof, so that you shall not cause blood [to be spilled] in your house, lest someone fall from there.” This seemingly obvious commandment is interpreted not just literally but figuratively to mean that one must take precautions to preserve the bodily well being of oneself and others. The Talmud Berachot and the scholar named Maharasha further interpret the verse “but beware and watch yourself [lit. your soul] very well”, also from Deuteronomy, as a precaution to guarding life. Smoking hookah, a now established health risk factor and the second highest risk factor for non-communicable diseases according to the World Health Organization, goes against the outlook of Torah. Hosting “Hookah in the Sukkah” parties promotes not just an unhealthy and risky behavior, it goes against the essence of Sukkot and Torah commandments.

I understand old habits die hard. The older generation, like those in my Persian family, may never let go of smoking hookah. They took part in this habit in Iran and their ancestors long before them did too. However, the new generation is one of statistics, scientific data, and a wealth of knowledge. According to Dr. Roger Detels, “smoking is a habit that starts young” and “the research that has been done on smoking finds that people who smoke do so by the age of 23.” Change and prevention begins with the youth. Today, we know the harm hookah puffs can do. Smoking is not a behavior, like eating chocolate or drinking wine, that is actually good in moderation. Smoking is harmful, as it damages internal and external organs and exposes the body to countless toxins. As a Jew, I believe it is my duty to educate those around me on what seems like a superficial and subtle issue but is actually a critical health and spiritual concern. For next year’s Sukkot parties, I suggest forgoing the party theme of “Hookah in the Sukkah” and instead opting for “Babkah in the Sukkah.” The latter also has a ring to it and is just as enticing and exotic, whilst within the parameters of Judaism.