Politics are a big deal everywhere, but they’re a huge deal at UCLA.

Student government candidates, for example, go to great lengths to promote their elections, swallowing Facebook feeds with flawless photos in front of Royce Hall and inundating Bruin Walk with campaign posters. School administrators, for instance, engage with state government leaders to discuss school policy and to lobby for more funding. Student media outlets endorse student government candidates in the same way national media outlets would endorse candidates for federal elections, perhaps thereby exaggerating the importance of student government. And student organizations, hoping to achieve progress in the policy areas about which they are most passionate, demonstrate on Bruin Walk, publish opinion pieces in student media outlets, develop social media campaigns, and … sabotage political opponents?

On Oct. 29, the Daily Bruin published an article exposing Hillel at UCLA’s consultation with 30 Point Strategies — a public relations firm — about how best to deal with a forthcoming student government resolution regarded by many in the Jewish community to be anti-Israel. The resolution calls for the UC to divest from companies in which it invests, that conduct business which profits from the alleged violation of Palestinian human rights. The article cited an e-mail exchange between Rabbi Aaron Lerner, senior Jewish educator at Hillel, and Arielle Poleg, media and client manager of 30 Point strategies.

While a host of questions arise from the situation, the issue is not the ethical or logical nature of divestment; nor is it the fact that a campus organization pursues outside help to protect the students it represents from foul invective and emotional abuse (of which some students involved in Hillel, anonymous per their requests to remain as such, were victims during last year’s divestment resolution). Rather, the issue with this entire controversy is the right to privacy. Before asking, “Why would someone oppose divestment, a movement that (purportedly) promotes human rights?” or “Why would a student organization consult and pay an outside organization?” the first questions anyone should ask are “How was this private, sensitive e-mail obtained?” and “Why would any media outlet publish the e-mail?”

According to the same article, the Daily Bruin obtained the e-mail from Alex Kane, an assistant editor at Mondoweiss, the self-described “liberal, progressive” Jewish news website that first broke the story. When contacted, Kane revealed that the email “was leaked” to Mondoweiss, but declined to comment on who leaked it.

Rabbi Aaron Lerner, the victim of the leak, expressed his belief that he was hacked, citing the “twenty character, randomized password and two-step e-mail verification” he uses to emphasize the difficulty anyone would have accessing his e-mail manually. The conclusion that someone accessed his e-mail by circumventing these protections seems plausible, since the only other way the e-mail could have been released was if someone copied on the e-mail had then shared it with the media. However, the only recipient of Lerner’s e-mail was an employee of 30 Point Strategies, which “does not comment on its client work,” according to a quote obtained by Mondoweiss from Josh Silberberg, director of public media at 30 Point Strategies.

Rabbi Lerner’s case, unfortunately, does not represent the only leak plaguing Jewish communal leaders at UCLA. Over the summer, after his personal e-mails and GroupMe messages were published in the Daily Bruin and the Daily Californian, student regent-designate nominee Avi Oved was accused of violating political campaign funding rules and proceeding to cover up his alleged wrongdoing. Unlike Rabbi Lerner’s case, it is unclear whether Oved’s private messages were accessed by a third party or released to a media member from an adviser or staffer privy to his account. Oved has since been confirmed as UC student regent, and told Ha’Am, as well as the rest of the UC community in an open letter published by UC Davis’ The Aggie, that he is ready to move forward. In his term, he hopes to achieve greater state funding for the UC and augment mental health resources across all campuses.

Despite Oved’s resilience and positivity, according to the Wallen & Klarish Law Corporation, California Penal Code Section 502 “criminalize[s] the unauthorized taking or copying of data and information from a computer, computer system, or computer network.” A breach of an e-mail account and dissemination of the private information therein, as in Lerner’s case, would clearly constitute an “unauthorized taking […] of information.”

However, even if Rabbi Lerner is somehow incorrect in his presumption that his account was hacked — which is unlikely given the lack of other plausible explanations for the leak — legally, Mondoweiss should not have published that private information. According to the Digital Media Law Project, an initiative produced by Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, private information is strictly protected under federal law and is only permissible to release to the public if it serves a “legitimate public interest.”

No matter how staunchly detractors may argue otherwise, a personal e-mail detailing Hillel’s specific organizational plans does not qualify as serving a legitimate public interest, because the release of the information in no way enhances the common welfare at UCLA, and it frankly does not clearly benefit anyone at all, much less a majority of the UCLA community.

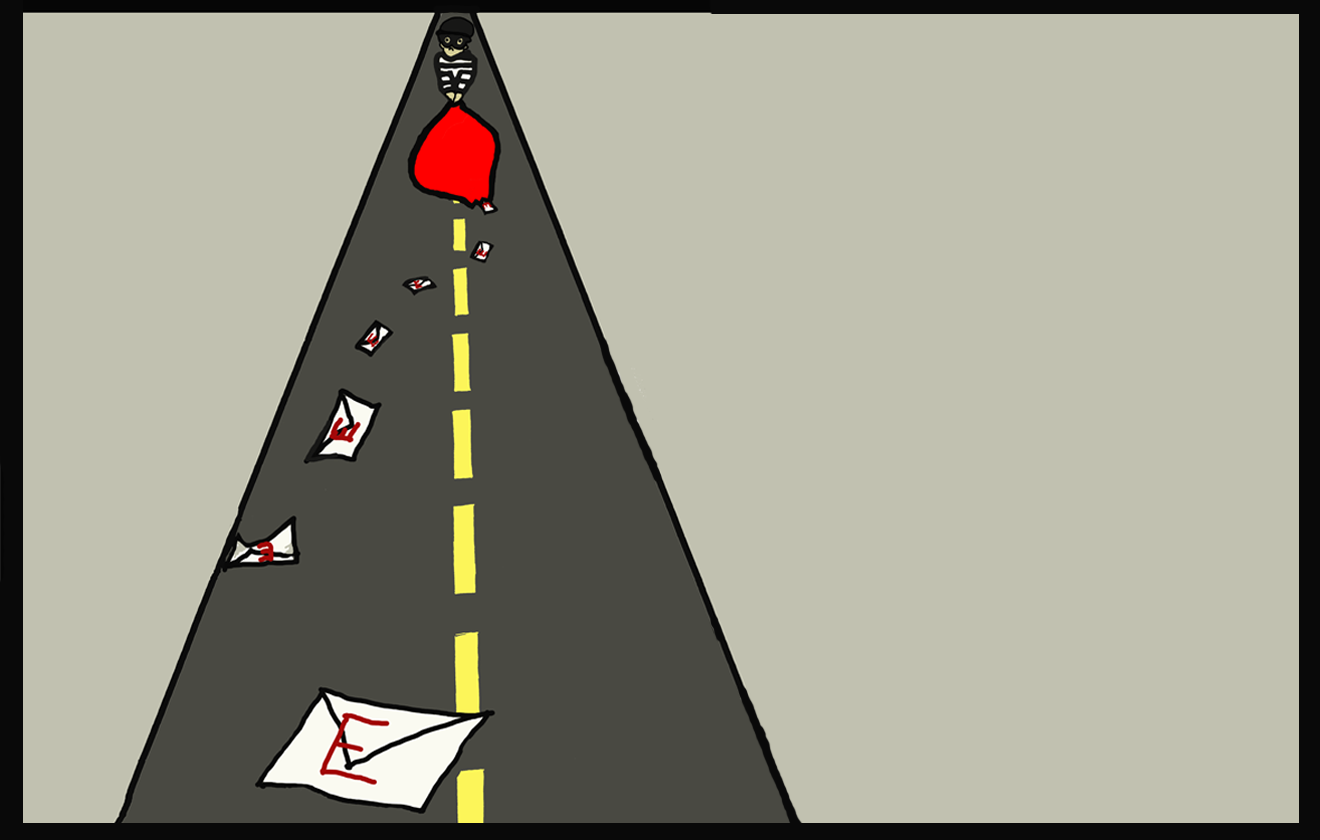

Still, even if the legal argument is not convincing, consider its ethical counterpart. Where are we as a school, even as a society, when the compromise of private information on a private e-mail account is justified to achieve a political objective? Presuming Rabbi Lerner was hacked by someone who champions the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement (as the rabbi and ample circumstantial evidence suggest), is pushing for divestment so important that its supporters will violate a basic human right in personal privacy?

And more, is it not egregiously ironic that a supporter of the BDS movement — which professes to champion human rights — violates one of the most fundamental and sacred human rights to privacy, just to make political progress?

There is no political cause great enough to justify the violation of the privacy of another individual. Privacy is a sacred right; it protects us from unfair judgement, it affirms our personal autonomy, and it preserves our human dignity. If any cause were great enough to justify the violation of privacy to advance it, every cause could be. Our society could look much less like an open domain in which ideas and thoughts can either be shared or withheld, and much more like an Orwellian dystopia in which nothing may remain personal. I am thankful our society does not currently resemble the latter condition, and am hopeful, despite this concerning chain of events, that we are not headed in that direction.